The art of war

Onosandri strategikos (Onosander's The general), translated by Nicolas Rigault. Printed in Paris by Abraham Saugrain and Guillaume des Rues, 1599.

Lower Library, G.20.13

Here is presented, in the original Greek with parallel Latin translation, Onosander’s Stratēgikos. The author is an obscure Greek philosopher of the first century A.D. credited with a commentary, now lost, on Plato’s Republic and this work, a treatise on the practice of good general-ship and the art of military strategy, made into Latin by Nicolas Rigault. It is divided into two parts: the first comprises the main text and the rather briefer Epitēdeuma of Orbicius; the second is Rigault’s notes and observations on the texts. How Onosander came to write his book we may never know; the identity of Orbicius is similarly mysterious but his Epitēdeuma (Inventum in Latin) is an account of the effective deployment of Roman infantry against the Barbarians.

Onosander’s work was influential. We are told that it was frequently consulted by the Byzantine Emperor Maurice (582-602) for his own writing. The Emperor is attributed with authorship of a late sixth-century manual of military planning, in twelve volumes, covering in encyclopaedic detail all aspects of the latest developments in effective Byzantine land operations, especially in the field of light infantry. The debt to the earlier source was such that its title, Stratēgikos, was unaltered.

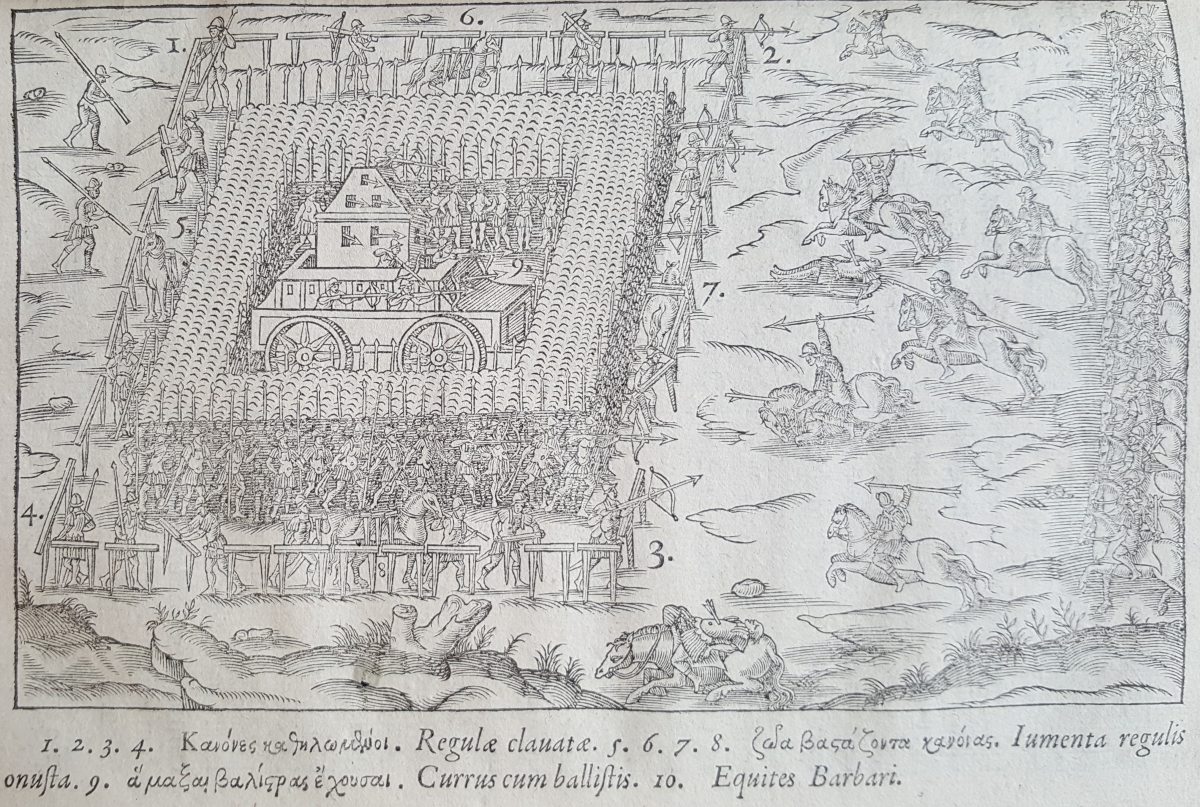

There are a number of interesting woodcut illustrations. In Fig.1 we see, in the Inventum, a foiled assault by the Barbarians, mounted on horseback, against the close-knit forces of the Roman Empire. The Roman crossbowmen rest on dainty wooden ledges and have already brought down a Barbarian horse. Two cavalrymen have been hit in the stomach. The highly disciplined Romans will wear down their enemy and then unleash, from their nerve-centre, a dreadful looking siege-engine that will smash all remaining resistance. The tree-stump in the foreground may be a portent of death.

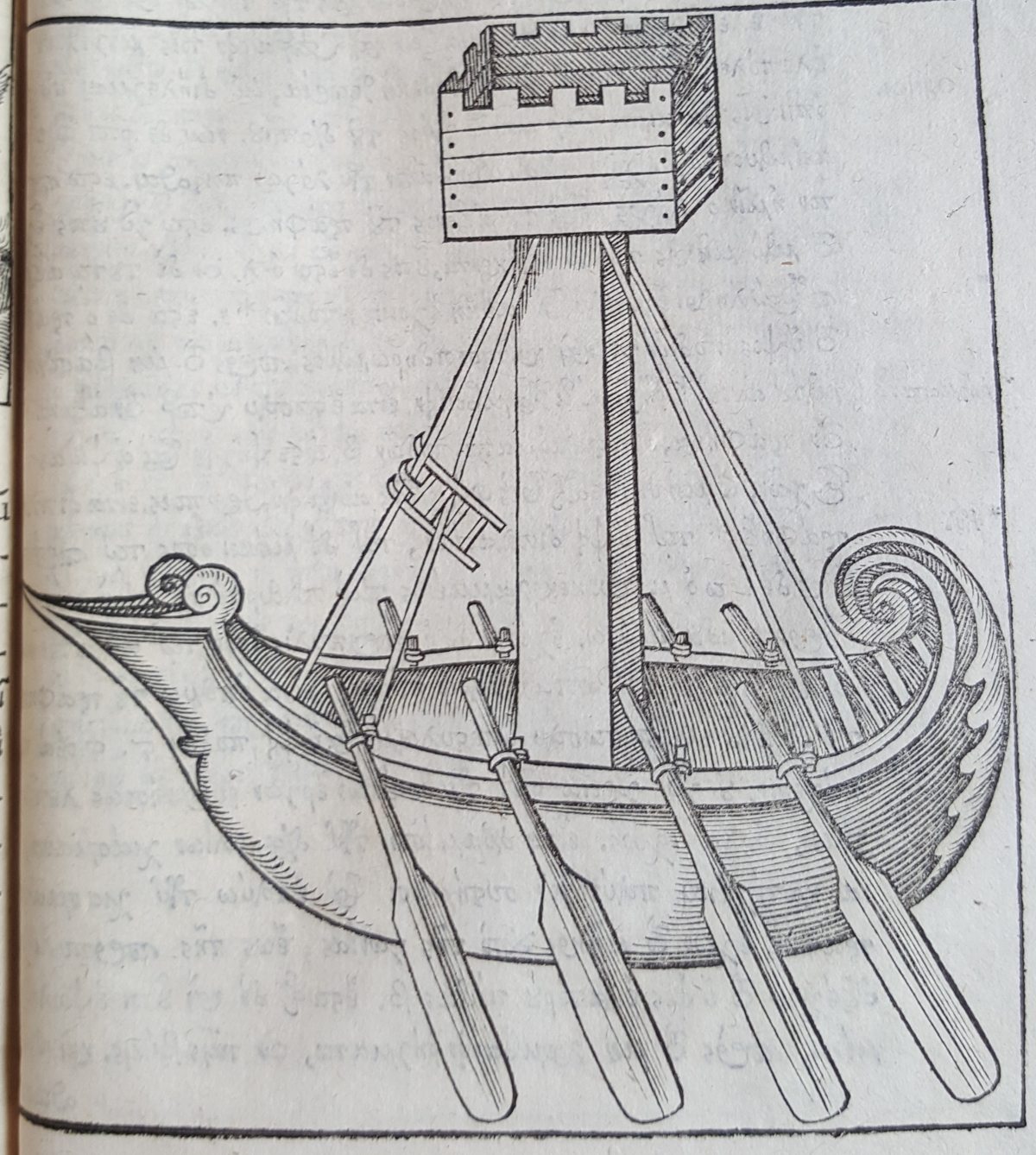

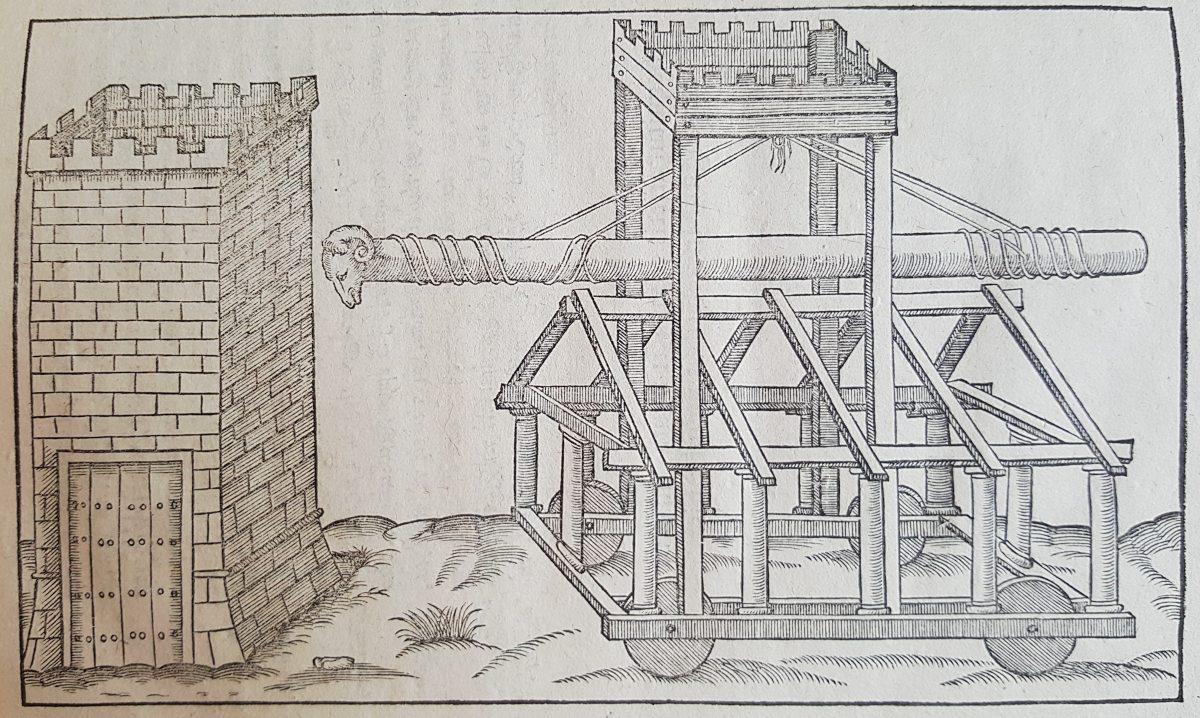

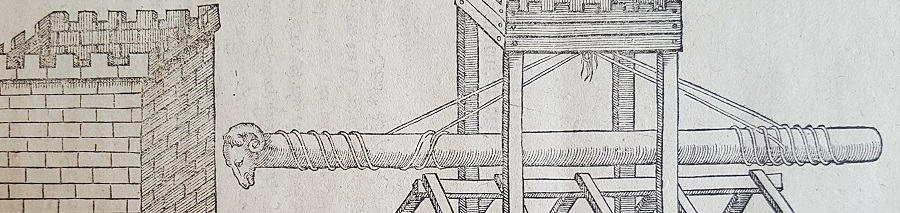

In the notæ there is a drawing of a battering-ram (Fig.3). The fort, with its right-angled corners, is of an Ottoman design. The ram, a tree-trunk, has an elaborately carved sheep’s head at its point. Ares was the Greek god of war and manly courage. We see also a militarised boat (Fig.2) and an itinerant fort on wheels with top-storey drawbridge (Fig.4).

Rigault dedicated his translation to King Henry IV of France (1589-1610), first monarch of the House of Bourbon. Following the lacklustre reign of Henry III, the new, and for a time Protestant, King secured several military successes against the Catholic League, most notably at the Battle of Arques (1589). Onosander might have admired the King’s willingness to lead in combat, if not the inelegance of his claim: 'on a le bras armé et le cul sur la selle' ('a weapon in one’s hand and one’s bottom in the saddle'). In 1610, stuck inside his horse-drawn carriage during a Parisian traffic-jam, the unarmed King was stabbed to death by a Catholic extremist; had he recalled his boast it might have been prudent to have travelled on horseback.