Second to the right and straight on till morning

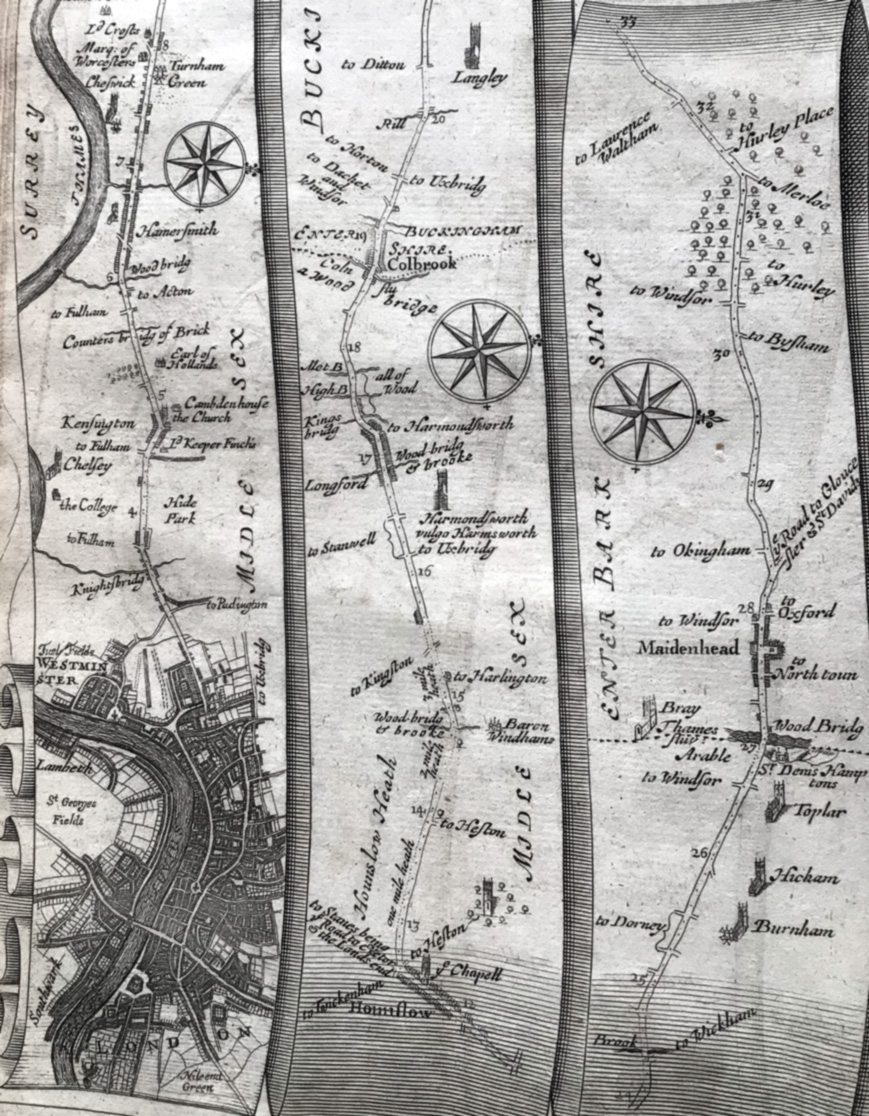

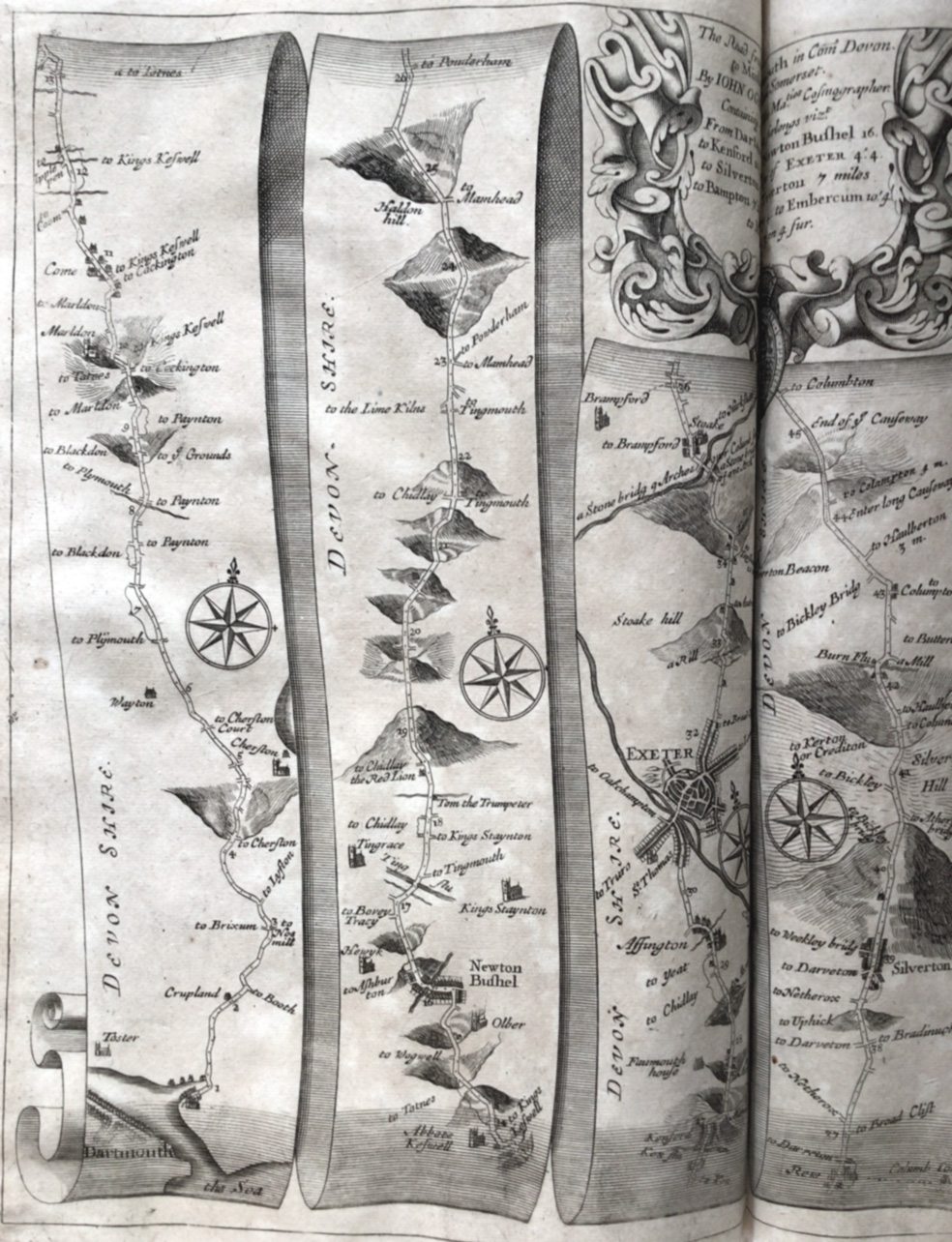

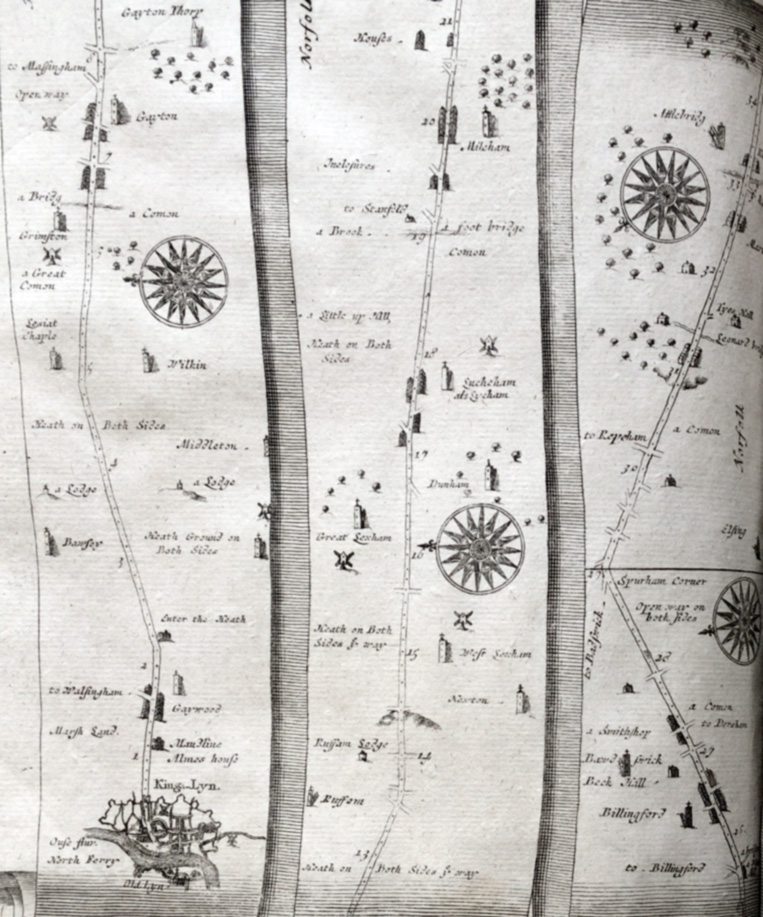

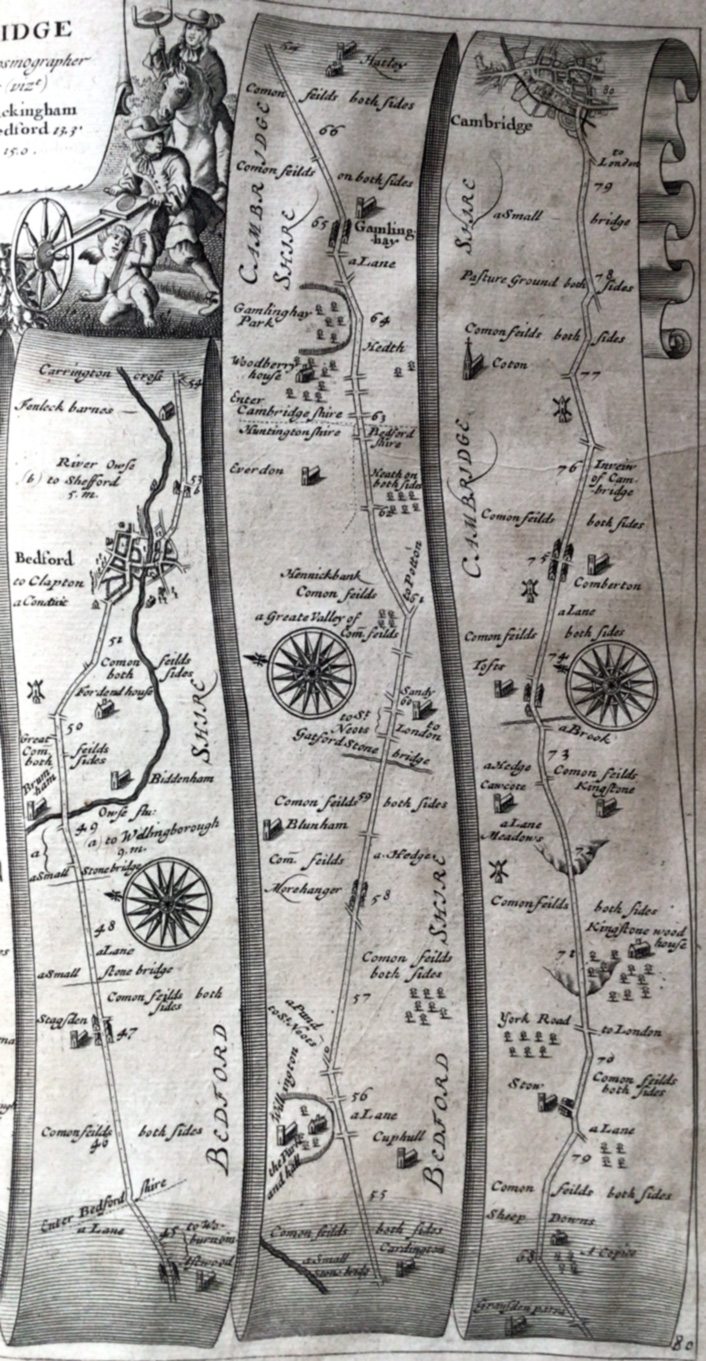

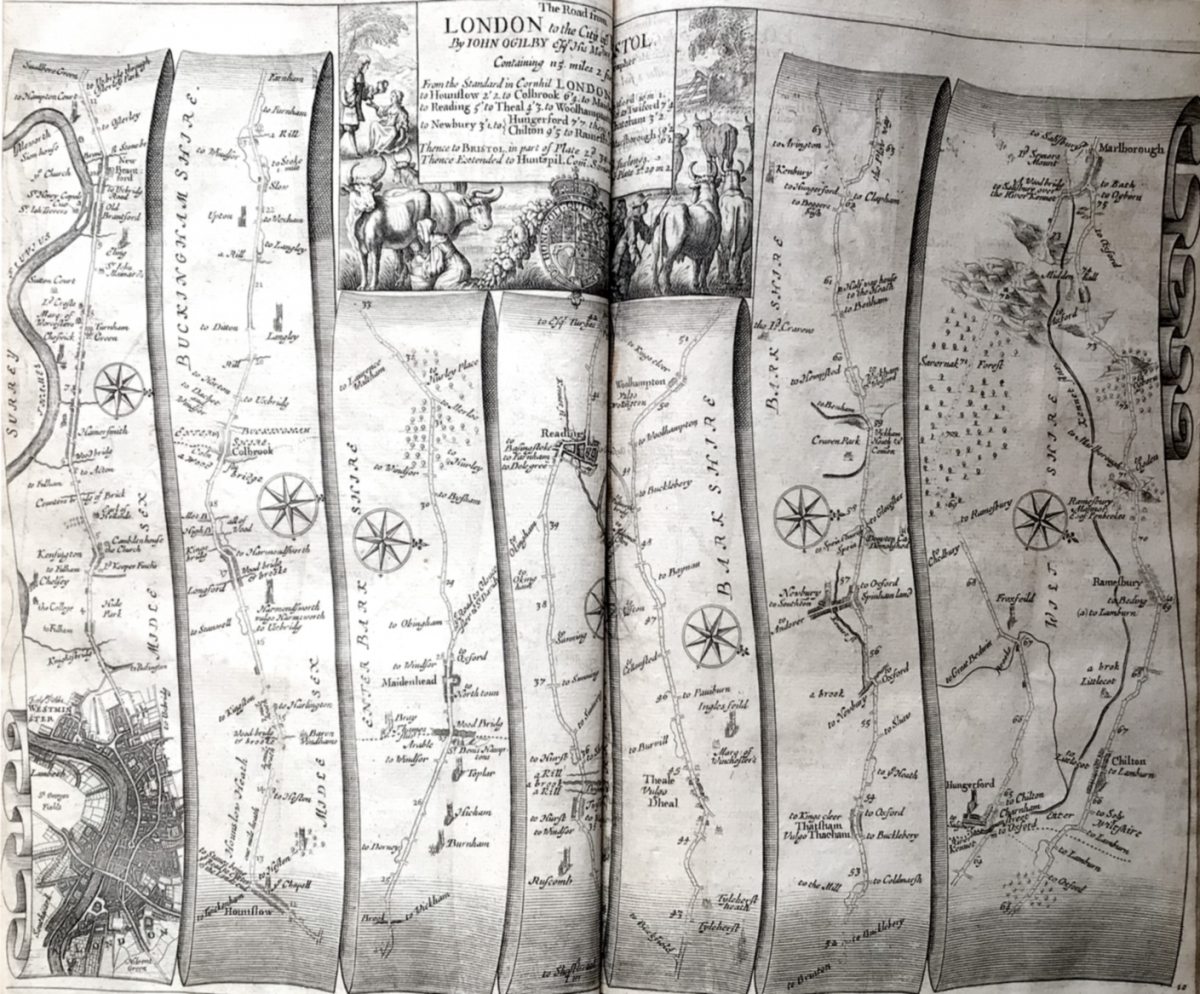

Britannia, or, The Kingdom of England and dominion of Wales, by John Ogilby, Cosmographer to King Charles the Second. Printed in London by Abell Swall, 1698.

Lower Library B.11.6

John Ogilby (1600-1676) was the first person to create a road atlas of England and Wales but he took an unconventional route into map making. His career as a dancing master and theatre owner in Ireland was cut short by the English civil war after which he settled in London and worked as a poet, translator and publisher. The Great Fire in 1666 destroyed his home and business but he secured an appointment by the City of London to survey the destroyed areas of the city in order to resolve property and land disputes. This work sparked an interest in cartography and after the resurrection of his publishing business Ogilby conceived a project to create a landmark five volume world atlas. He gained sponsorship from King Charles II, collaborated with Robert Hooke and other members of the Royal Society to devise accurate methods for measurement, and secured John Aubrey and Gregory King as surveyors. Ogilby intended the volume on Britain to be expanded into its own major work but limited by financial constraints and his age (Ogilby died within a year of Britannia being published) only the first volume, mapping the roads of England and Wales, was completed.

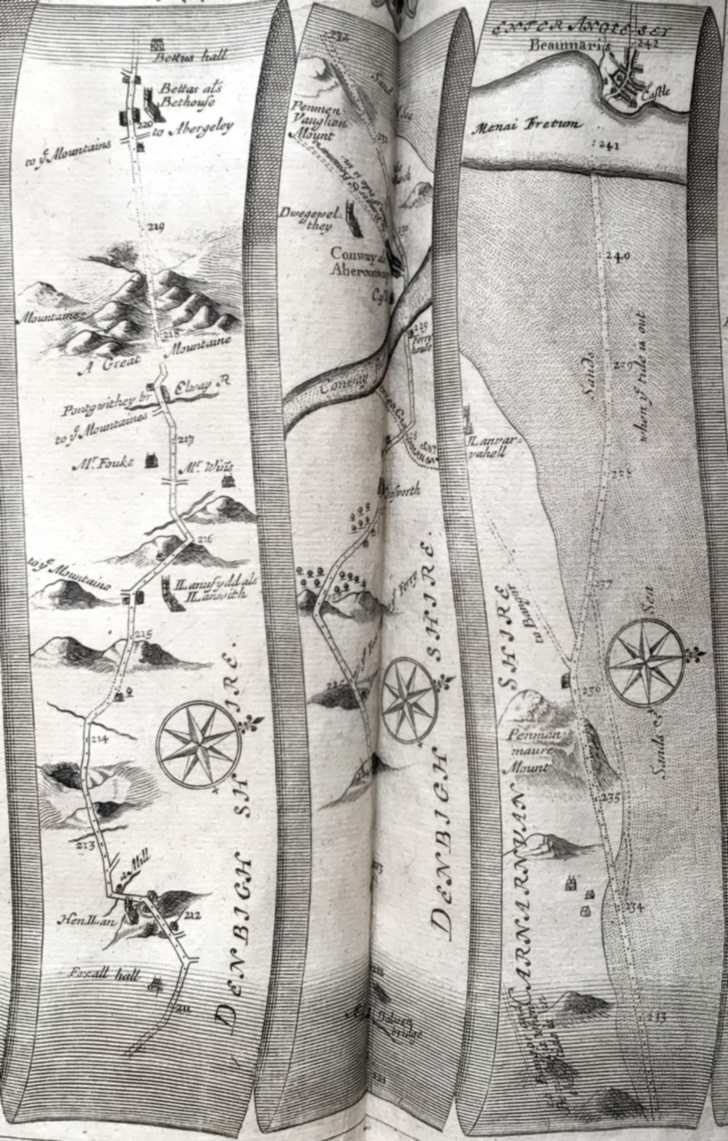

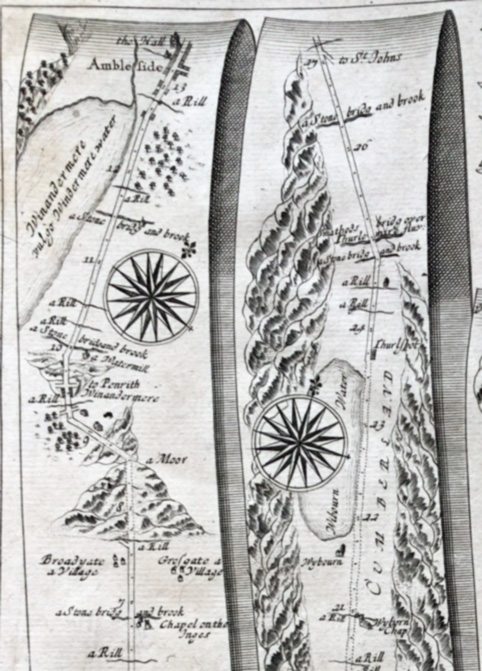

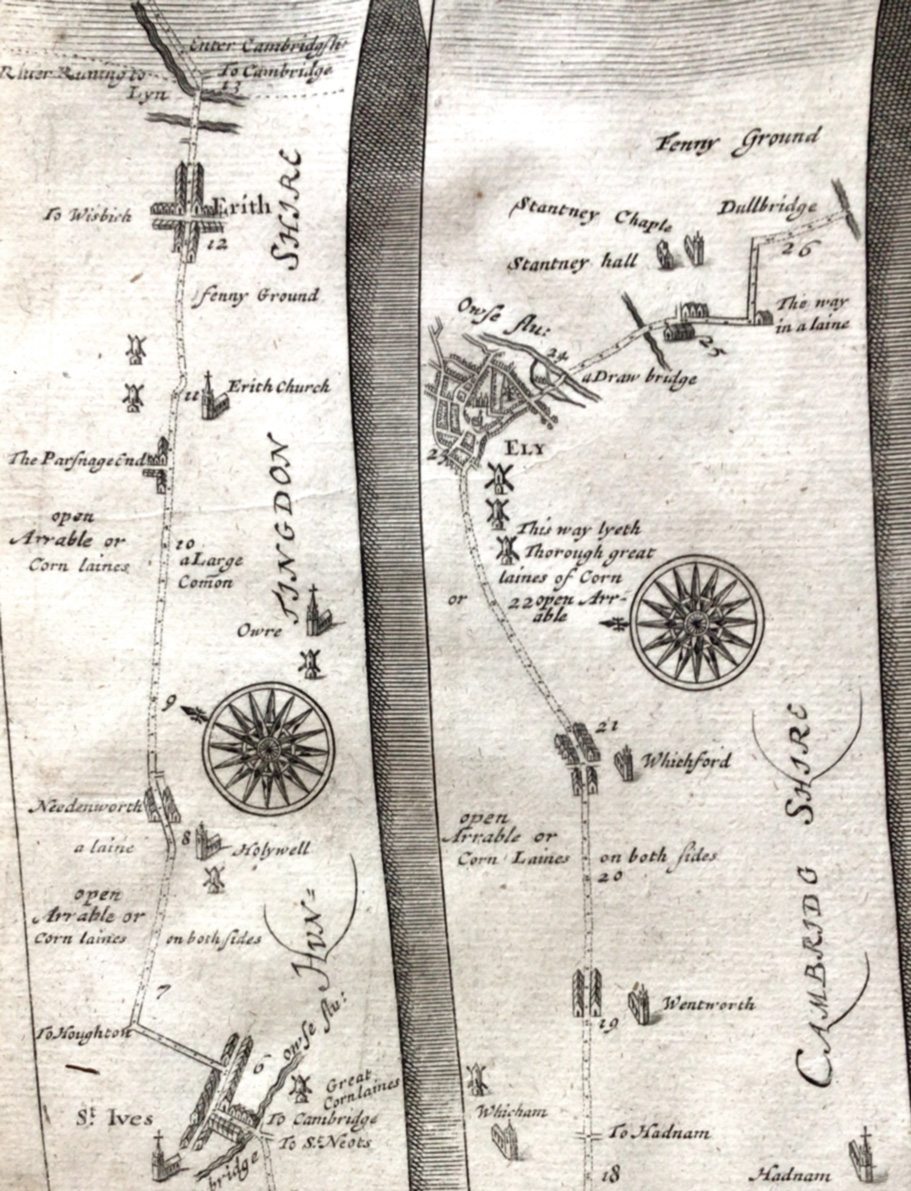

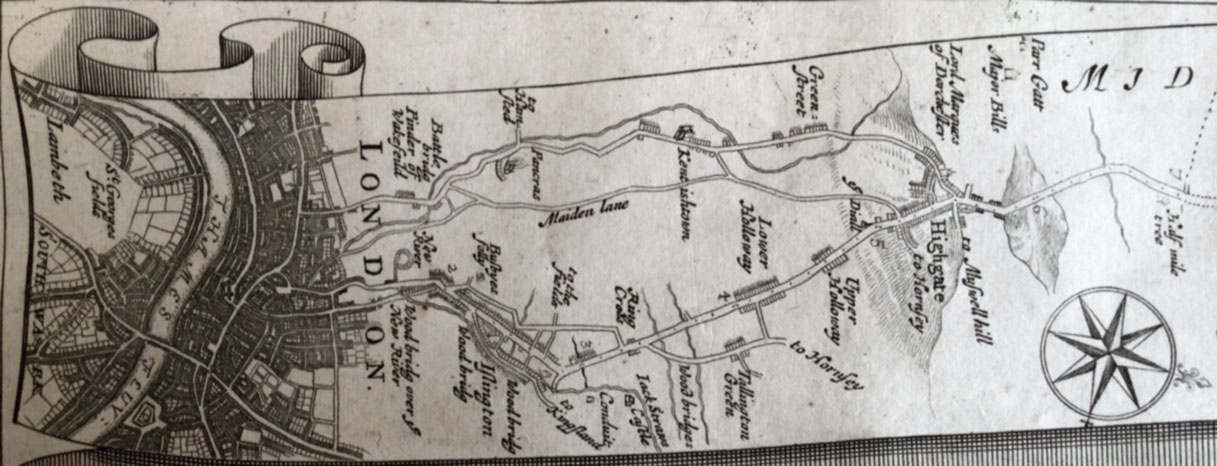

Using a compass and odometer to take standard measurements the surveyors produced a scale of one inch to a mile, the same as the first Ordnance Survey maps published in 1801. Prior to Britannia route maps had existed since the medieval period but they could be as simple as a list of locations in sequence with no distances or measurements. Ogilby’s maps were not just intended for direction but also for tourism and include symbols for villages, churches, inns, industries, major houses etc., topography and local points of interest, reflecting the way people traditionally navigate by landmarks and notable features.

While highly decorative the strip map form forced constraints onto the draughtsmen who had the difficult task of converting the original surveys into a fixed narrow rectangle a couple of inches wide. This means some of the careful and accurate work of the surveyors was lost, for example the shape and direction of the road was sometimes manipulated or artificially straightened, the length of the road was altered and some features were moved, placed in the opposite direction or avoided altogether. Names were another source of confusion and there are frequent errors.

Nevertheless Britannia remains an impressive achievement, covering 7,500 miles of the seventeenth century road network in detail. The form of the maps are also unusual; these are strip maps portioning the main road with its branches into segments and would usually be pocket sized for portability. Presumably Ogilby’s choice of a large format means Britannia was intended as a reference work for patrons to consult at home, and some owners had colour added by hand. Each map covers a full page spread with 6-7 strips, or several sets of pages for long routes - a complete colour set of the plates can be viewed online.