Incunabulum conundrum

Ortus Sanitatis

[Strasbourg : Johann Prüss, about 1507]

Lower Library: L.18.21 (G.A.S., 102)

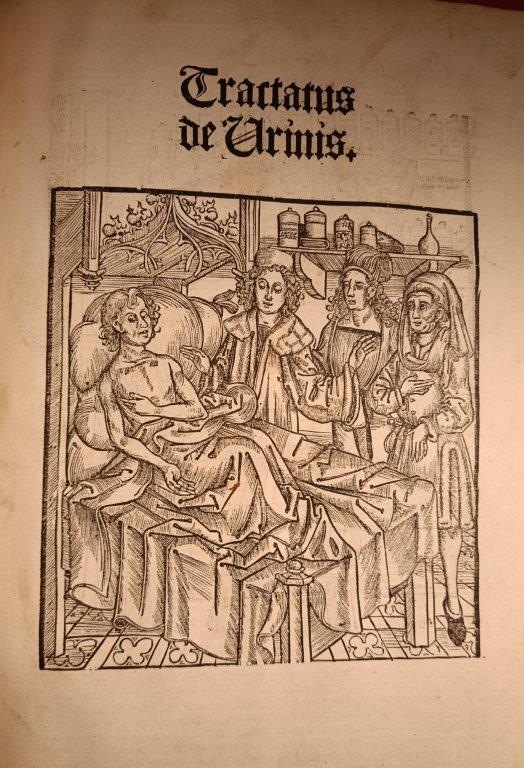

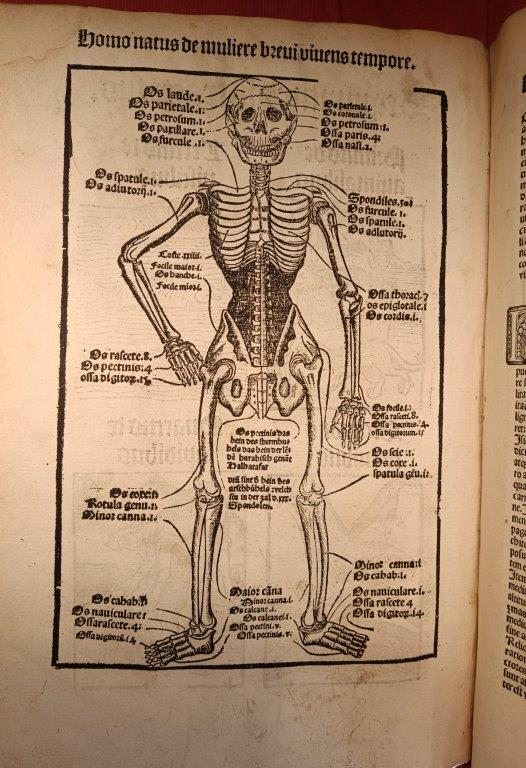

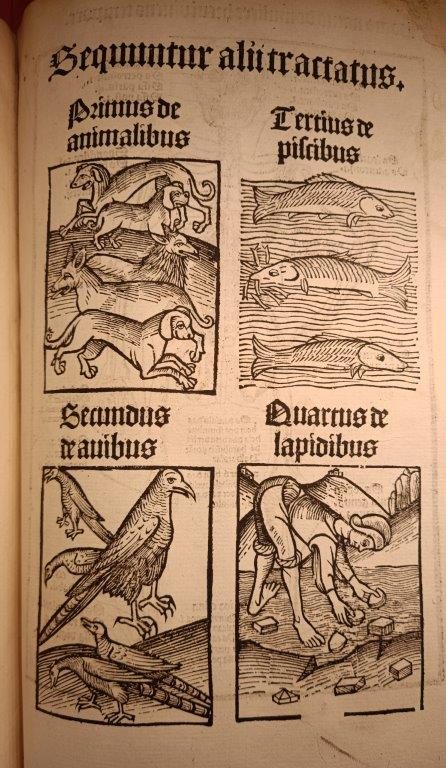

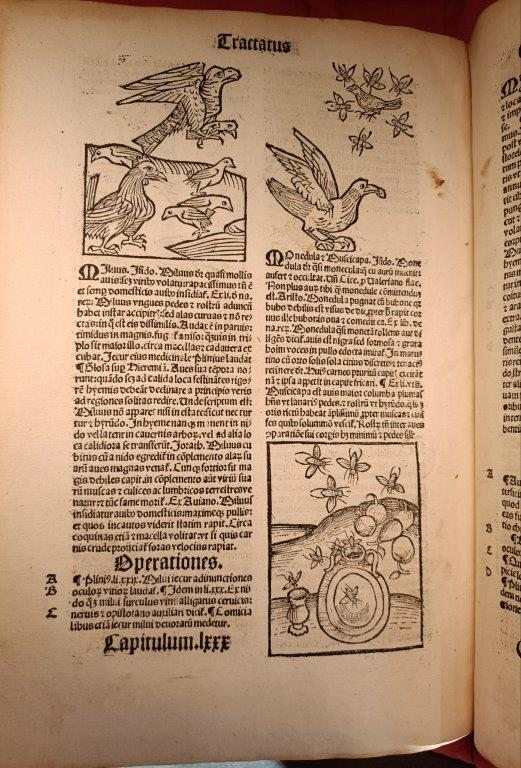

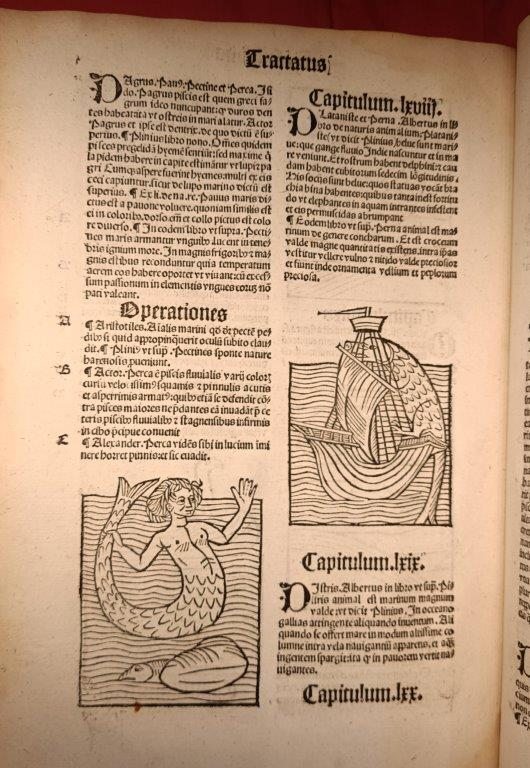

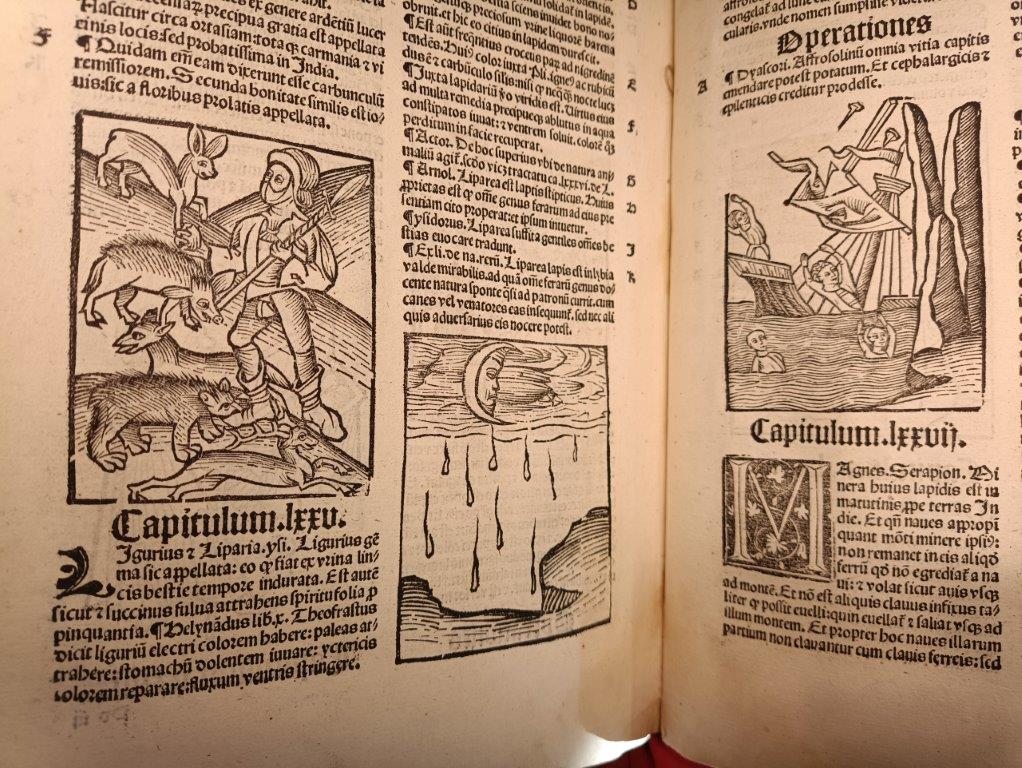

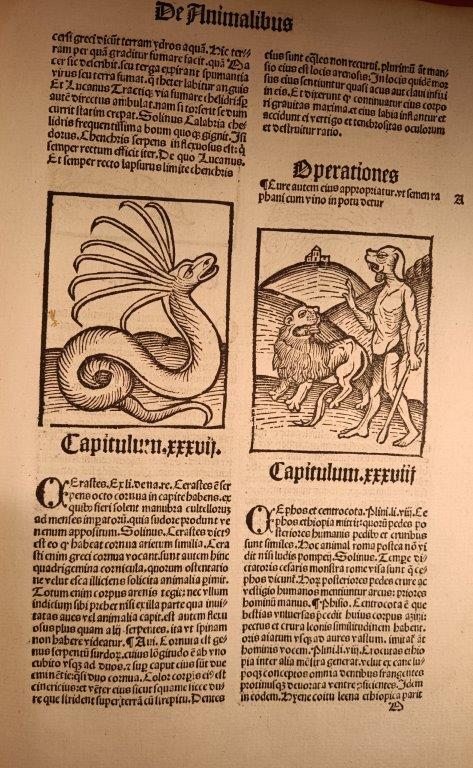

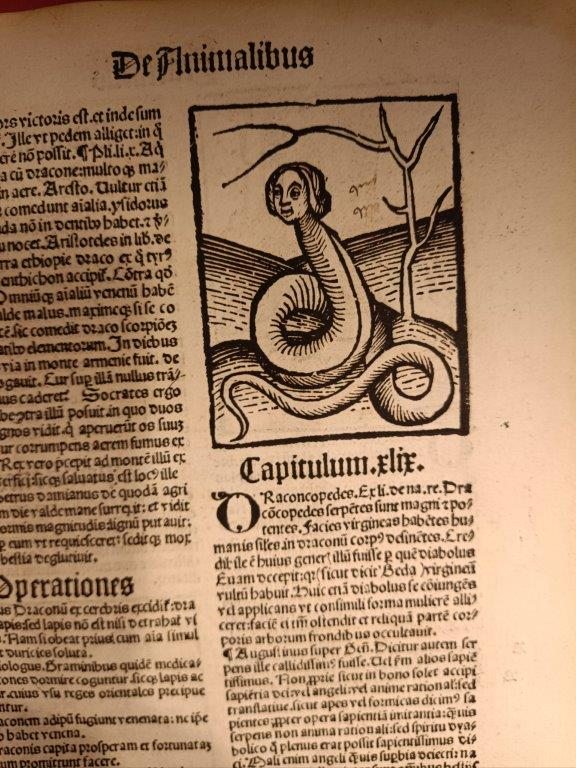

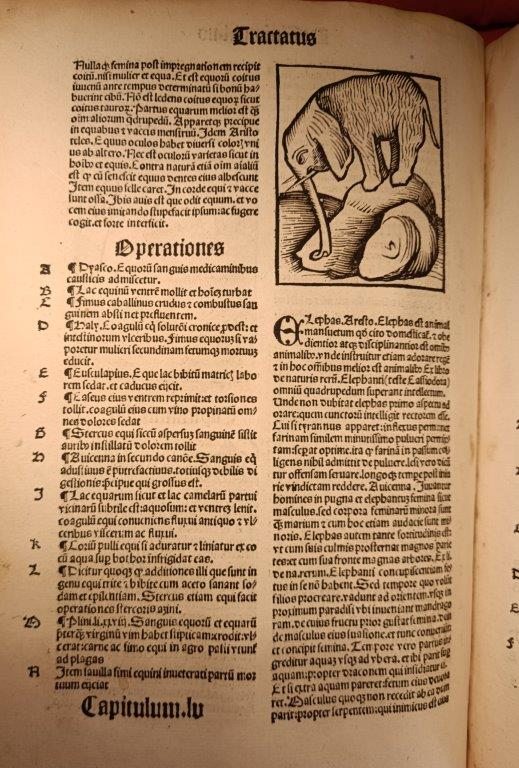

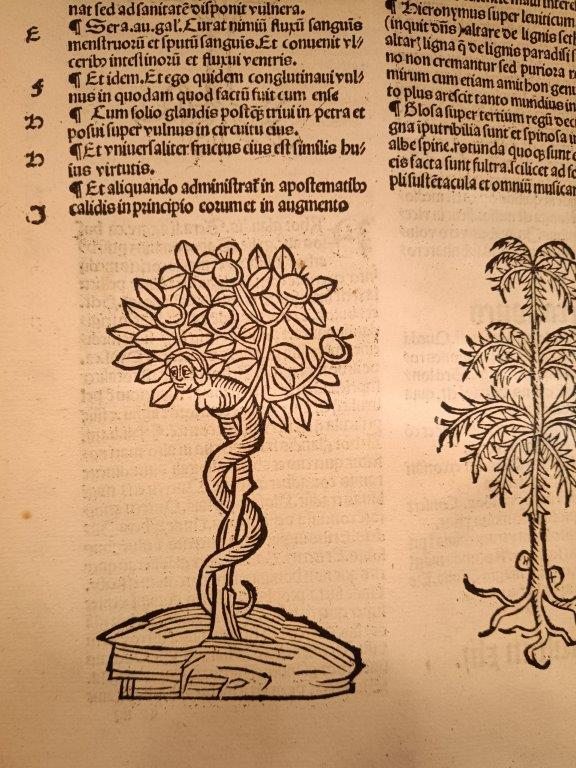

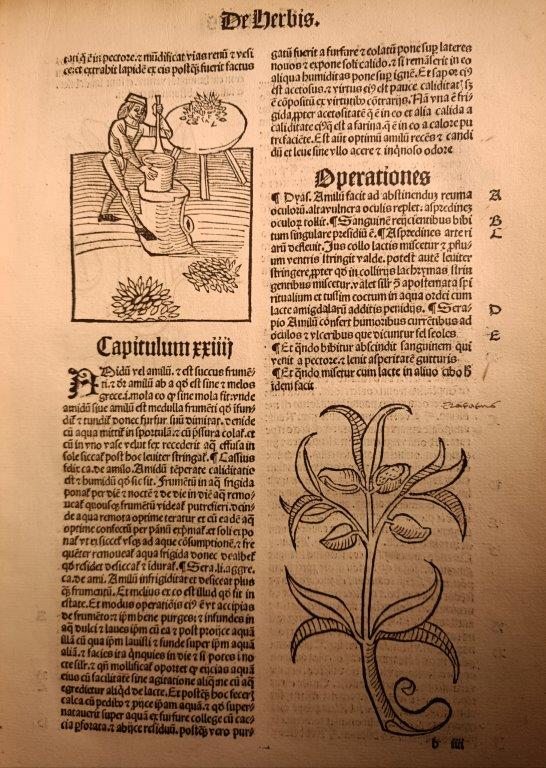

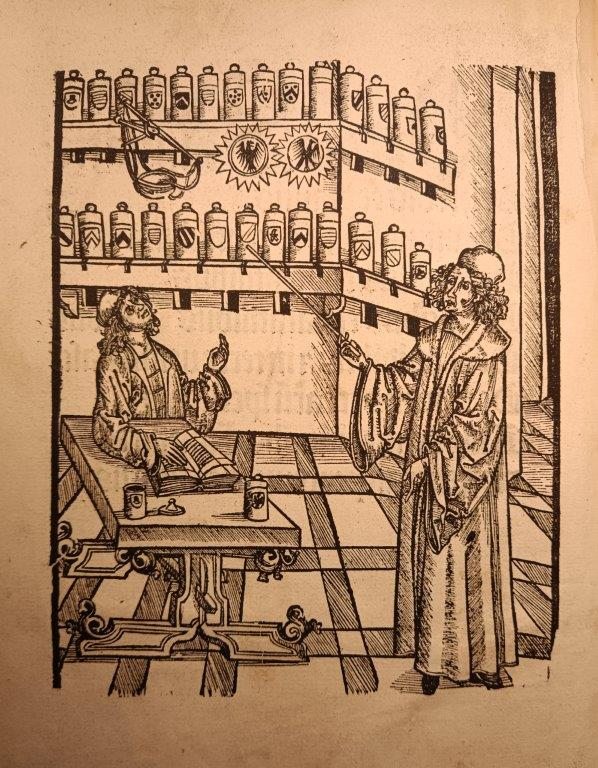

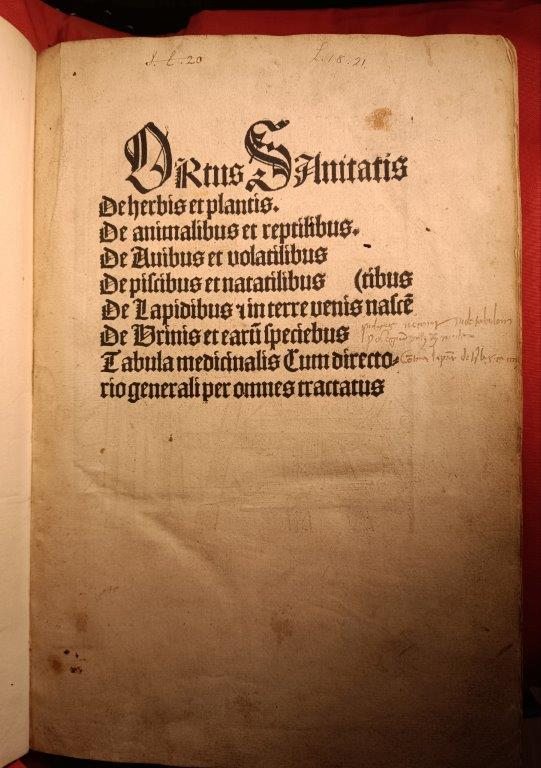

The Hortus Sanitatis (‘Garden of Health’) could be considered the first encyclopaedia of natural history. Two earlier such books had dealt with plants, but this one, first published by Jacob Meydenbach in Mainz in 1491, adds sections on mammals, fish, birds, and rocks—all with their corresponding medicinal properties—and concludes with a final section on the diagnostic qualities of urine. Although many of the plants and beasts described are immediately recognisable, the work also includes many fantastical additions, including mermaids, zitirons, dragons, harpies, phoenixes, basilisks, myrmecoleons, mandrake men and the bausor tree, all of which are described as actual creatures and plants.

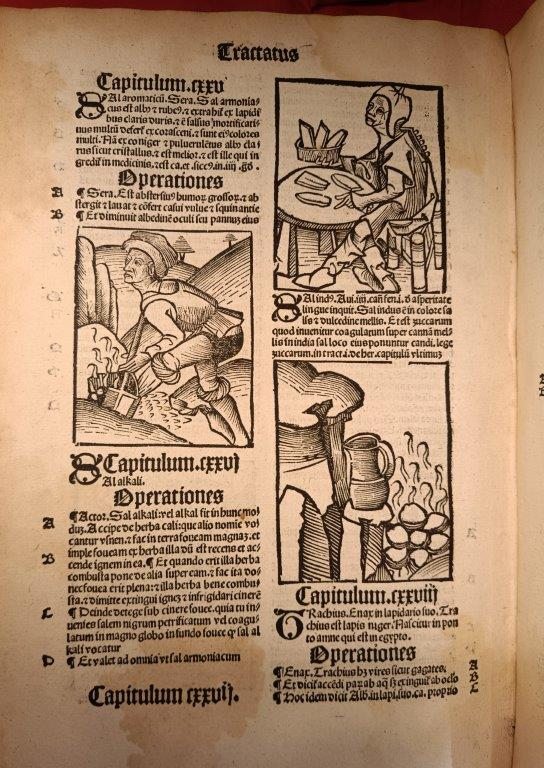

The book’s influence was wide, and it appears to have been a popular success, being soon reprinted in several editions and translations, and becoming a standard reference work in the early modern period. It has no known author — as is common with herbals of this time — and is heavily illustrated with over 500 highly characterful woodcuts.

Although the copy at Caius can be confirmed with some confidence to be the fourth edition of the work, being the third of those printed by Johann Prüss in Strasbourg, it nevertheless remains an open question whether it can confidently be called an incunabulum. For this to be the case it would have to have been printed before 1501, and while there is much to recommend the neatness of limiting the definition in this way, reality is seldom so tidy, and there is much ambiguity when it comes to works such as this with multiple printings that straddle the turn of the century. The various bibliographies of early printed books have no consensus, and while it is most commonly dated 1499, it is assigned various other dates between 1498 and 1510, depending on the source.

One way in which we can at least be sure this copy is from no earlier than 1497 is that the woodcut of an onion shows evidence of having been damaged by a piece of fallen type — taking the form of a little blank rectangle in the image — which is known to have happened during the course of the printing of Prüss’ first edition. This, at least, does not rule out the possibility of its being a true incunabulum. There is, however, an additional clue that this work may in fact have been one of Prüss’16th-century productions. Although the typeface and layout are seemingly identical with the 1497 printing in every respect, the earlier edition prints only small guide letters for the initials — a practice inherited from manuscript production, allowing them to be elaborated later by hand — as do other works printed by Prüss beyond the turn of the century. Instead, this copy bears woodcut initials — a trait shared by works known to have been printed by him in the 16th century.

Nevertheless, for now, all we can say with any certainty is: neither incontestably, nor inconceivably, is this book an incunabulum. It remains a conundrum.