Fixing the heavens

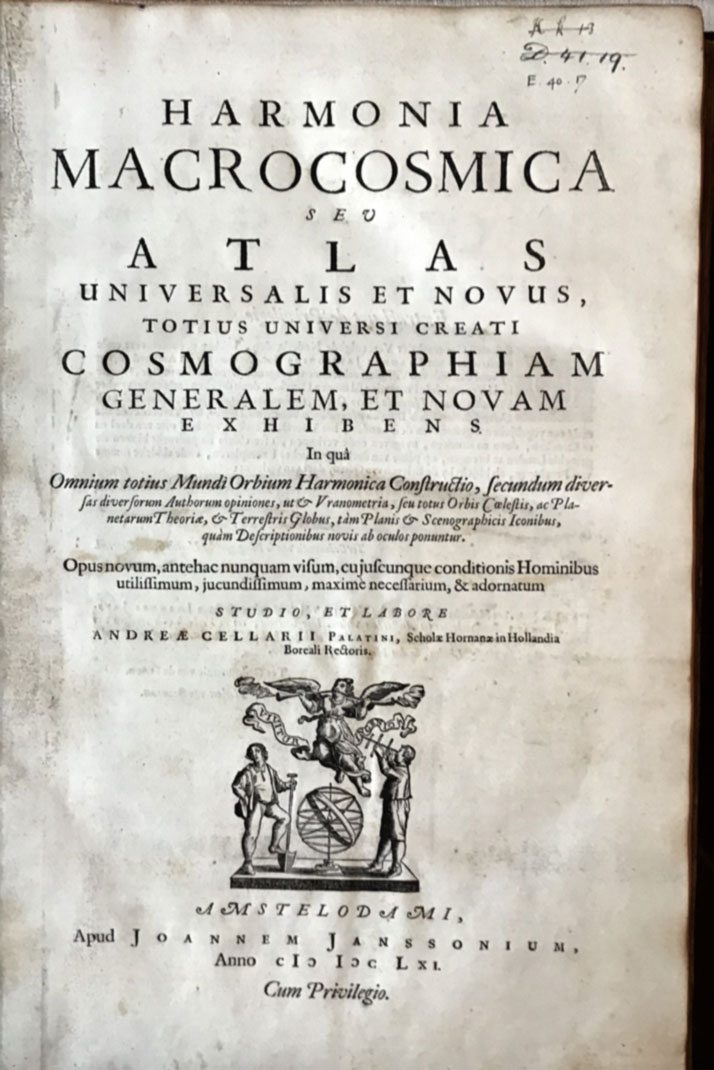

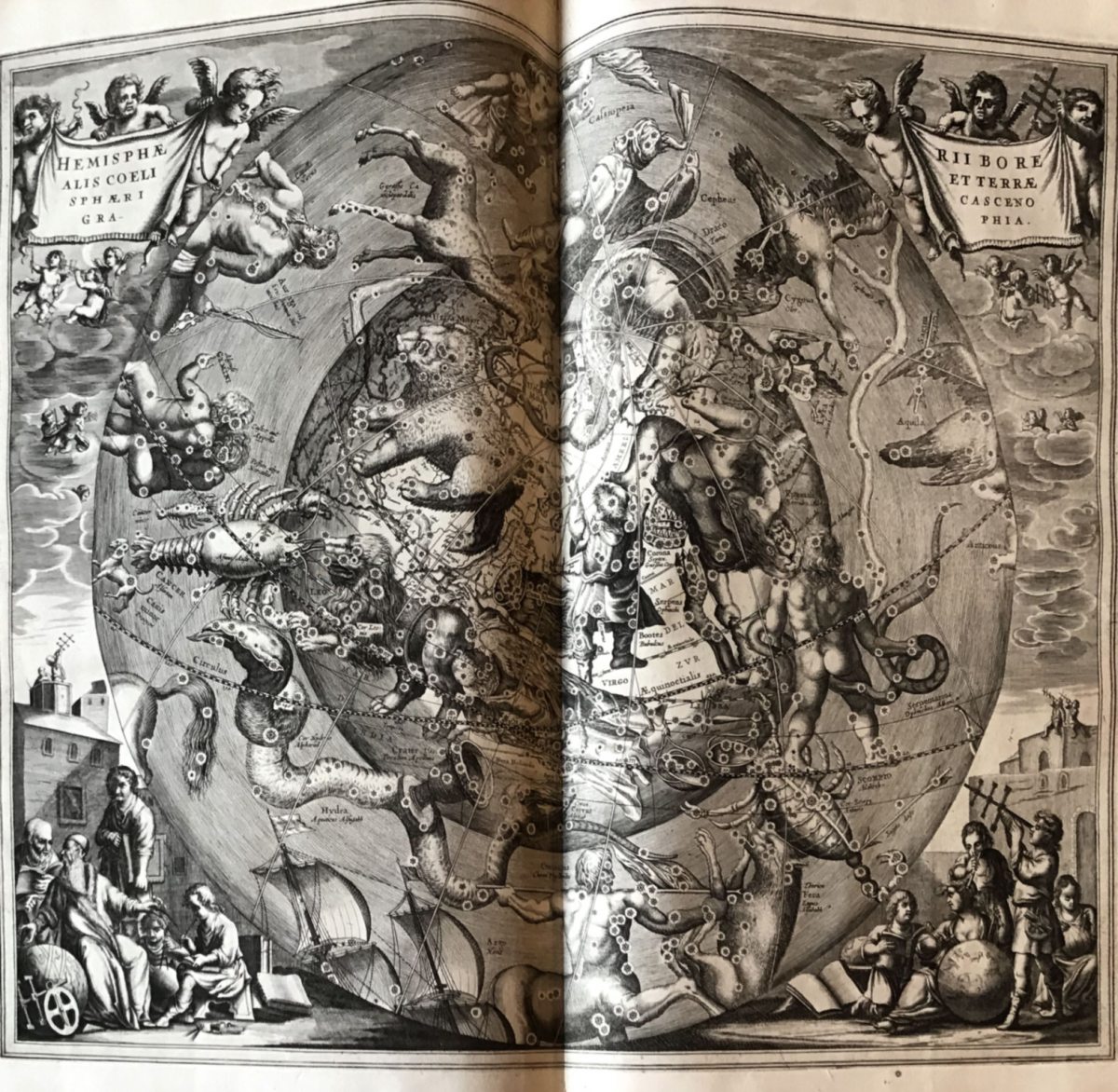

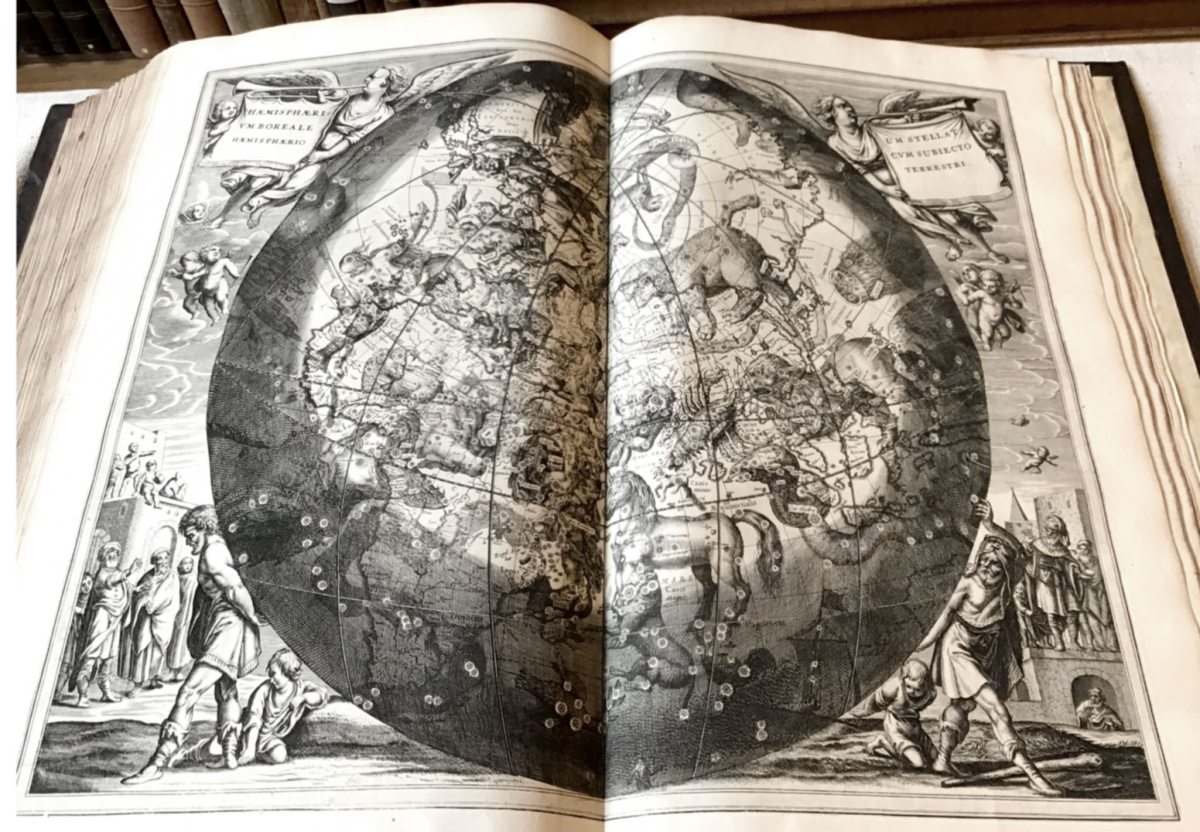

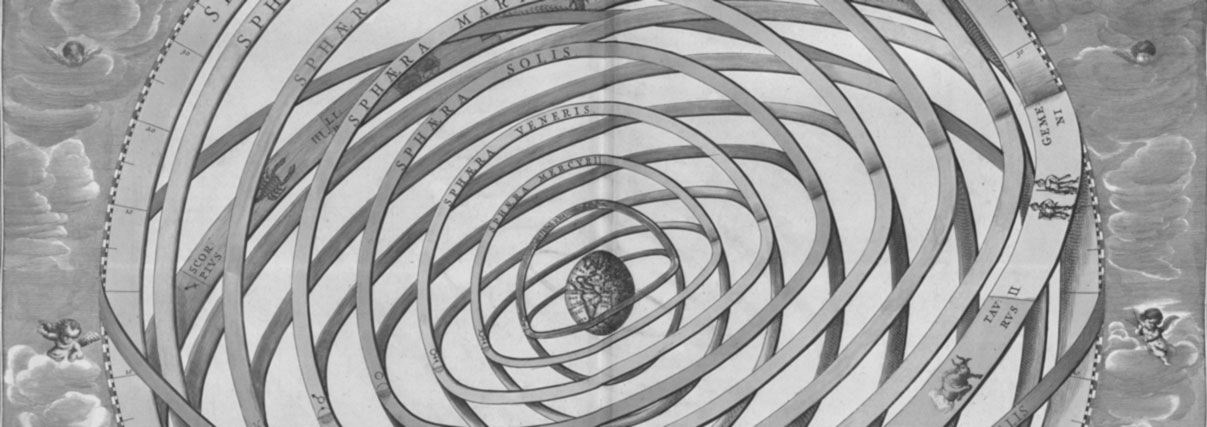

Harmonia macrocosmica by Andreas Cellarius. Printed in Amsterdam by Johannes Janssonius, 1661.

Lower Library, E.40.17.

During the Age of Discovery, the expertise of Dutch shipbuilding, seafaring and navigation enabled them to become prominent explorers, voyaging extensively and developing or applying new methods (such as triangulation) to maritime and celestial cartography. They were the first to reach and map remote areas of the globe like Svalbard, New Zealand, Australia and Easter Island. Establishing vast commercial networks, the Dutch incorporated their discoveries into new maps and grew to dominate the map making industry throughout the 17th century; now considered the Golden Age of Dutch cartography.

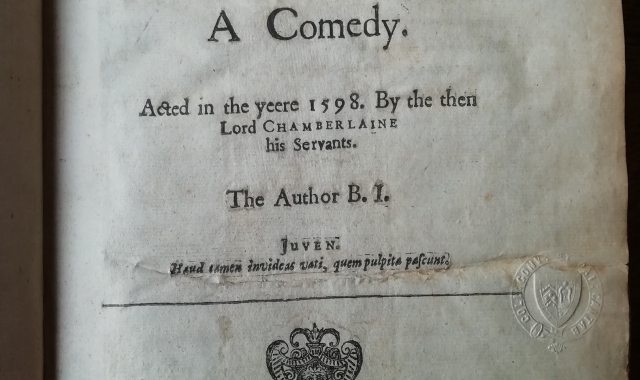

Historically, maps were created and sold individually as sheet maps, often purchased by wealthy individuals for display as works of art. Copperplate printing could reproduce good quality maps quickly but were uncoloured though hand colouring could be added after printing, usually by the owner. The first bound Atlas of uniform, engraved maps appeared in 1570 - Abraham Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World) and in 1662 perhaps the most significant work of this period, Joan Blaeu’s Atlas Maior, was published in Latin, with 600 maps in 11 volumes; you can view the Caius Library copy.

Although the Dutch were the first to systematically map the southern skies only one celestial Atlas was produced in the Netherlands during this period, the Harmonia Macrocosmica, created by Andreas Cellaruis. Details of Cellaruis’ life are sparse, he was born around 1596 in Neuhausen, Germany and attended the University of Heidelberg. He worked as a schoolmaster in Amsterdam and in 1637 became the rector of the Latin School in Hoorn, Holland where he stayed until the end of his life.

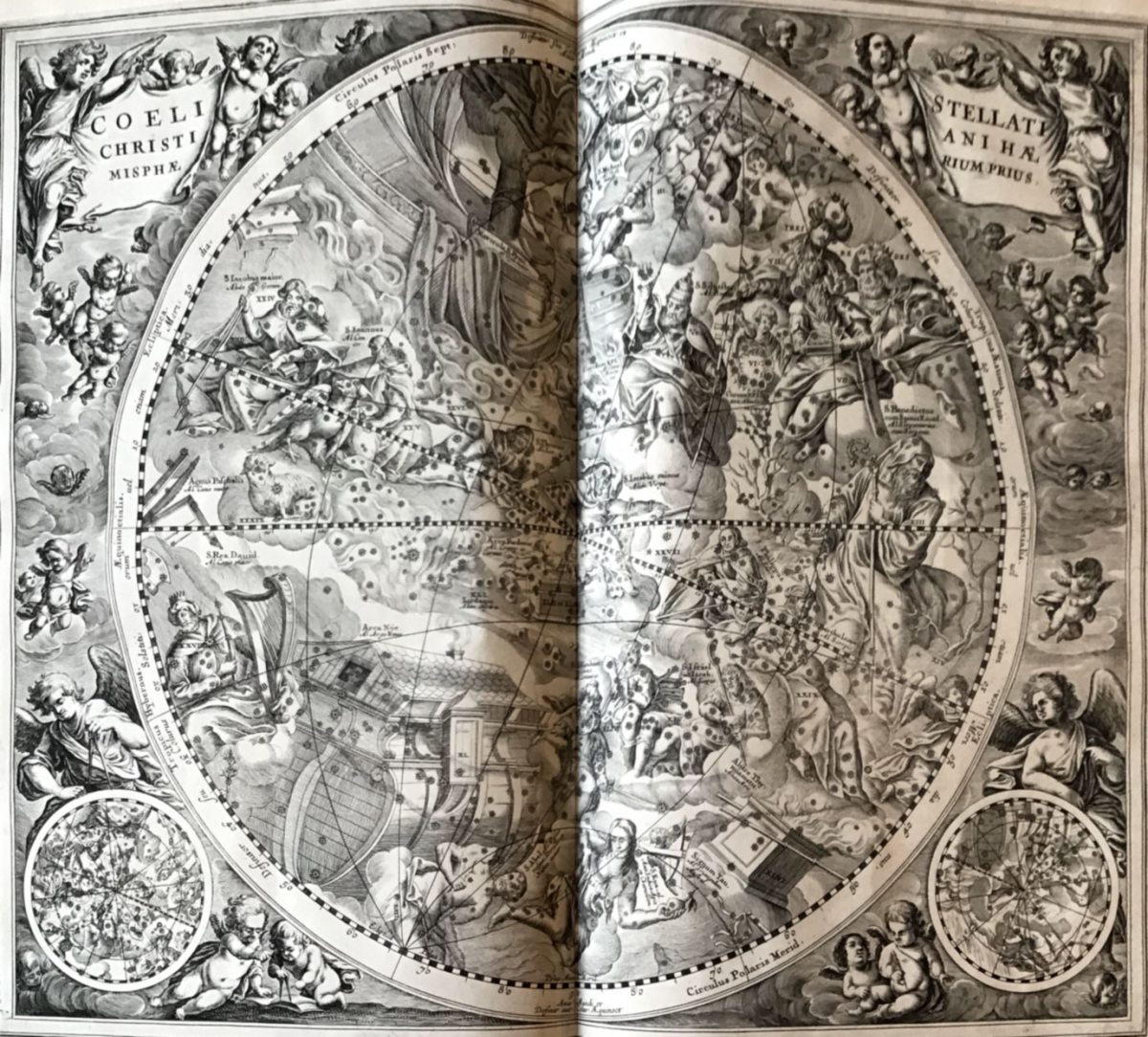

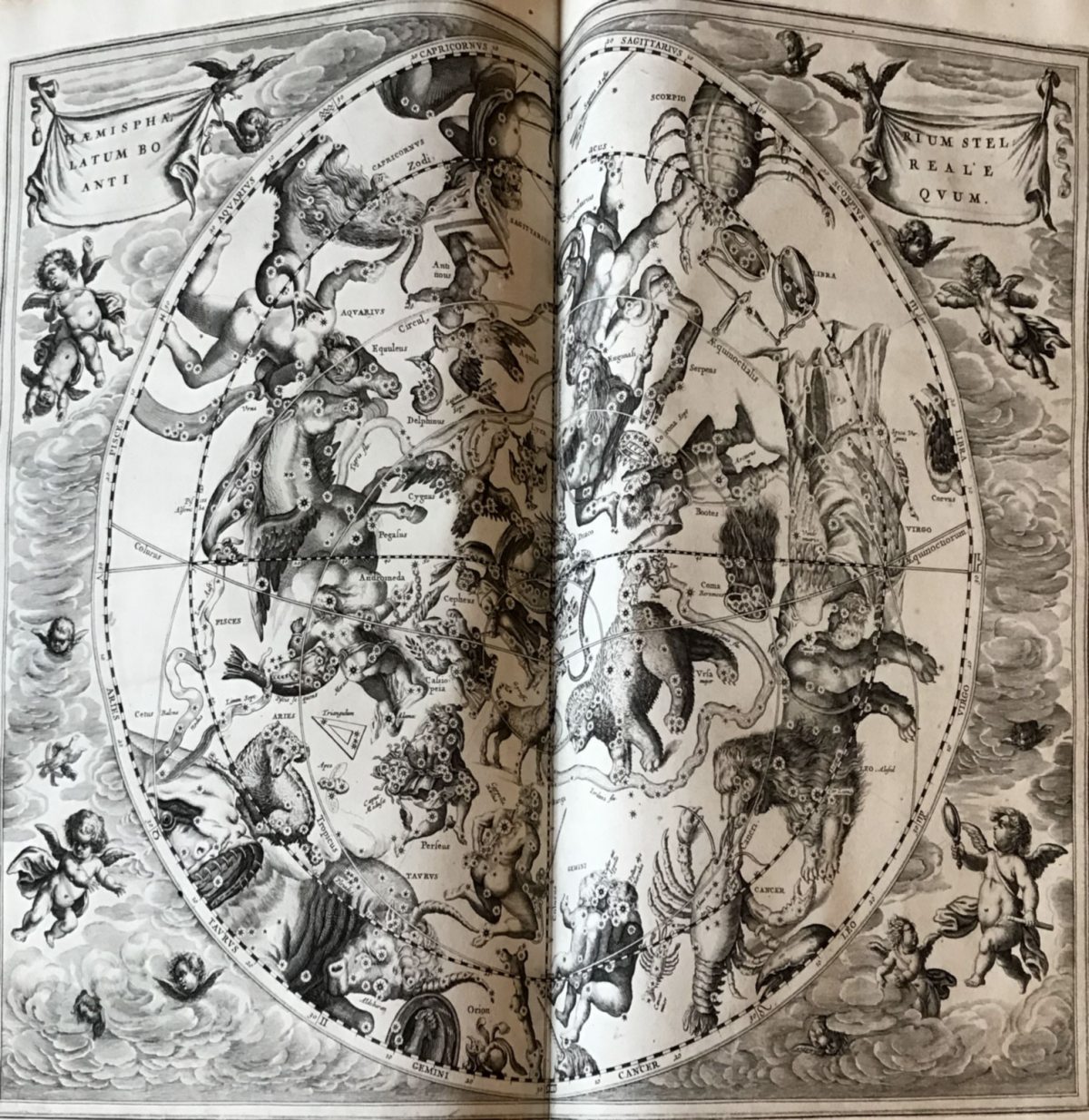

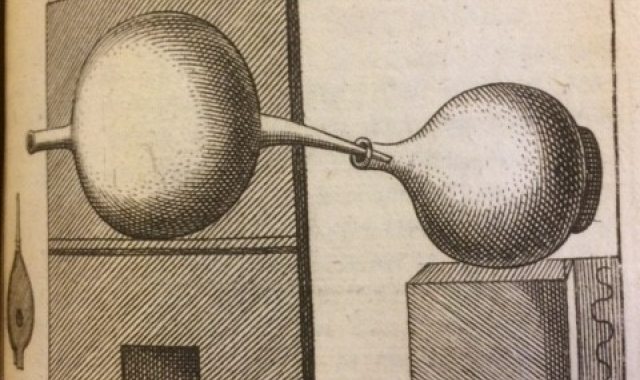

The Harmonia Macrocosmica illustrates the three contemporary planetary models: the Ptolemaic system where the Earth is at the centre of the Universe, with the sun, moon and planets orbiting around it, the Copernican model which places the Sun at the centre of the solar system with the Moon orbiting the Earth, and the Tychonic model which compromises between the two theories, suggesting that planets orbit the Sun but the Sun and Moon orbit the Earth. At this time the Copernican heliocentric model had not yet become the accepted theory and the final 8 plates also depict the constellations from classical mythology and in biblical forms.

At its publication the Macrocosmica was regarded more as a work of art than of science, particularly because of the ornate Baroque style of its 29 plates which sacrificed accuracy for the aesthetic, although it was notable for its scope in depicting the entire structure of the world. Only two engravers signed their plates, Johannes van Loon and Frederik Hendrik van den Hove who contributed the frontispiece. However, a shift from artistic to accurate celestial maps would soon occur after improvements to the telescope in the late sixteenth and early seventeen centuries. The Macrocosmica remains highly valued both as an object of beauty and as a work of significance in the history of celestial cartography where science, religion and art still intersect.

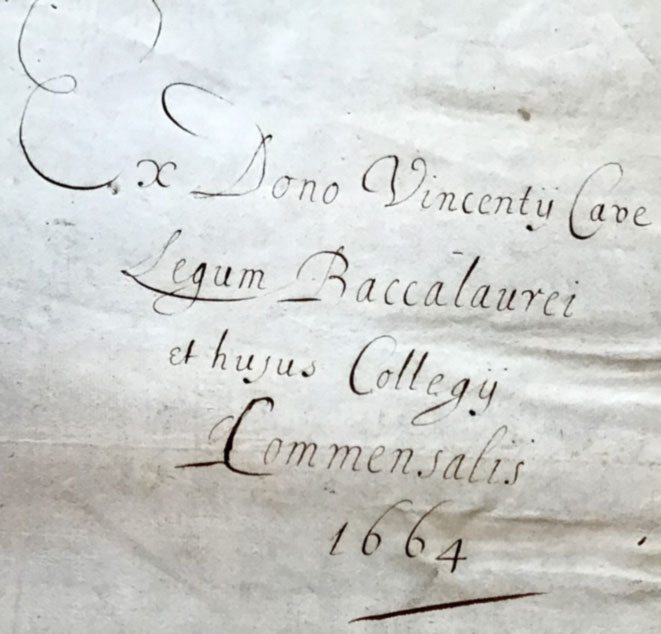

The copy in Caius Library was the gift of former student Vincent Cave in 1664, and features his inscription on the front flyleaf.

Follow the link for full colour images of the plates.