Some considerations about witchcraft

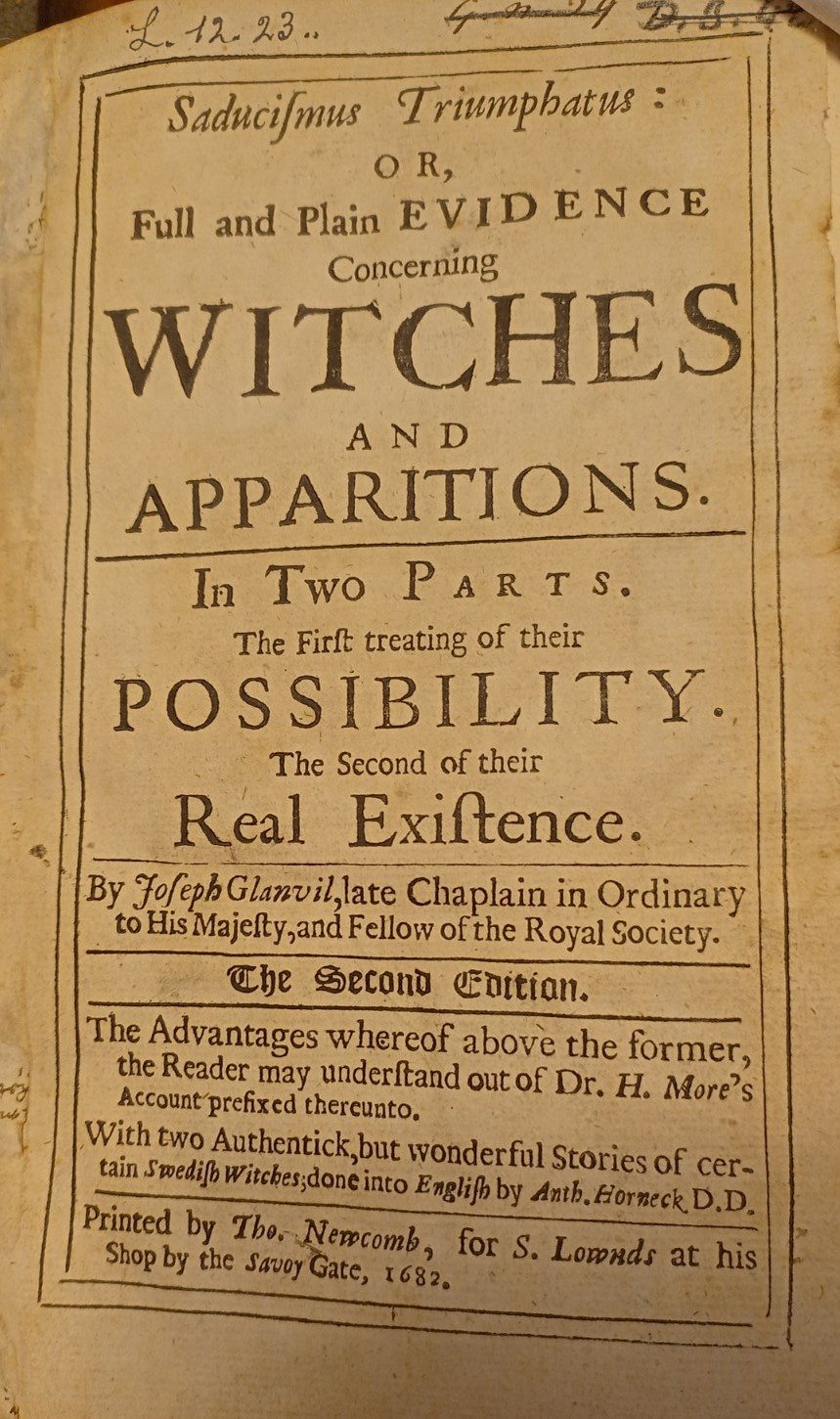

Saducismus triumphatus, or, Full and Plain Evidence Concerning Witches and Apparitions, by Joseph Glanvil.

[London: Thomas Newcomb, 1682]

Lower Library L.12.23

“The Question, whether there are Witches or not, is not matter of vain Speculation, or of indifferent Moment; but an Inquiry of very great and weighty Importance.”

Joseph Glanvill (1636-1680) was a clergyman in the Church of England, and a member of the Royal Society. He believed that atheism and superstition could be disproved by the study of science. In service of this belief in 1666 he began publishing his arguments for the existence of witches. Glanvill’s complete work was published posthumously in 1681; Caius Library holds the 1682 second edition. Saducismus triumphatus, or, Full and Plain Evidence Concerning Witches and Apparitions aims to prove the existence of a spiritual realm by proving that evil spirits exist. The title, Saducismus triumphatus, refers to the Sadducees, an ancient Jewish sect who denied immortality and the existence of angels. Glanvill uses this to describe those who only believe in a material world. He travelled the country to gather evidence of the supernatural, interviewed and credited witnesses, and did all he could to prove that events could not be explained any other way. Describing one incident, he notes:

“I searcht under and behind the Bed, turned up the Cloaths to the Bed-cords, graspt the Bolster, sounded the Wall behind, and made all the search that possibly I could to find if there were any trick, contrivance, or common cause of it; the like did my friend, but we could discover nothing. So that I was then verily perswaded, and am so still, that the noise was made by some Daemon or Spirit.” (Ff7, p. 81)

Glanvill also emphasises that he is not compiling these observations for entertainment:

“I have no humour nor delight in telling Stories, and do not publish these for the gratification of those that have; but I record them as Arguments for the confirmation of a Truth” (E7v).

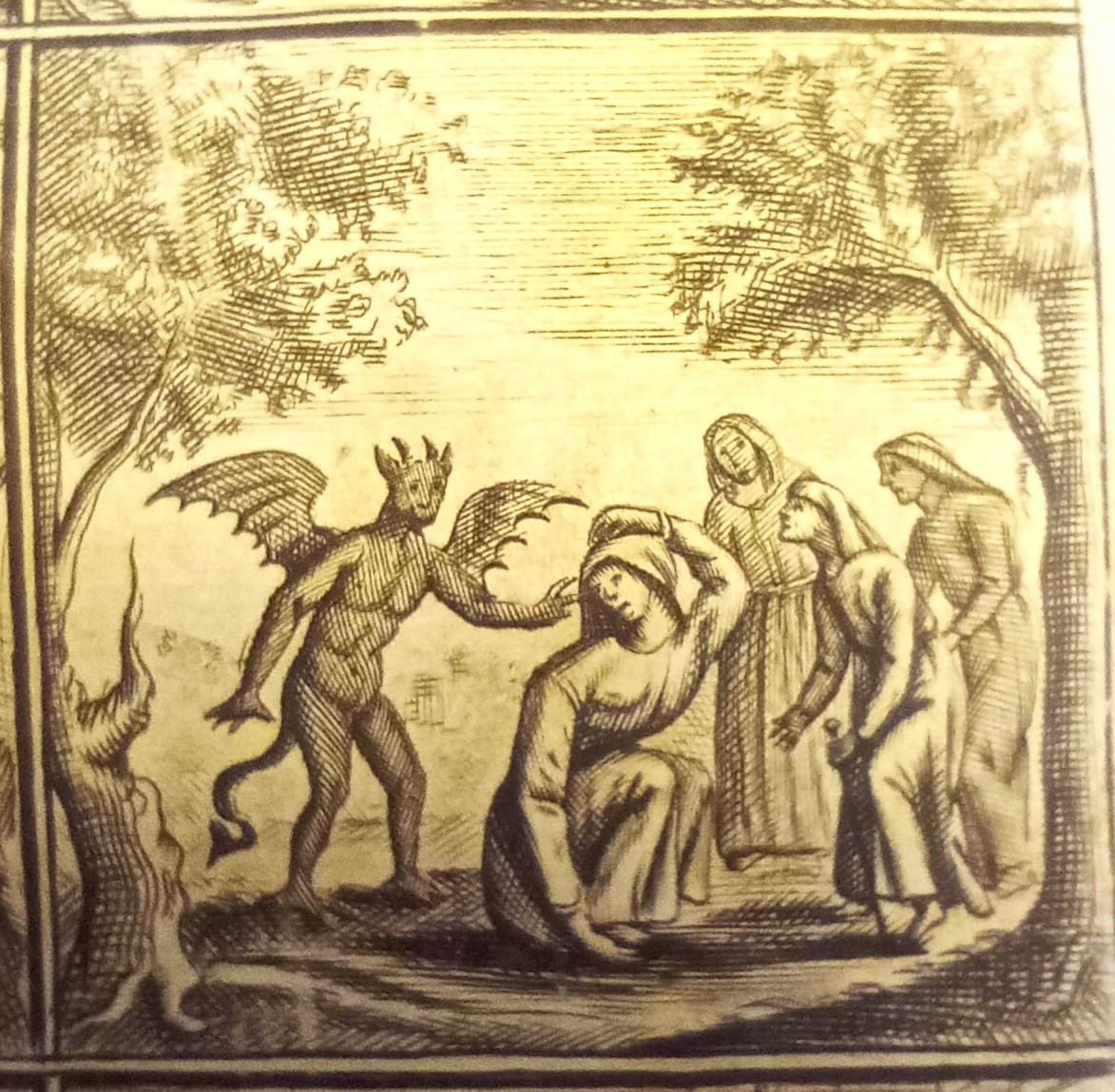

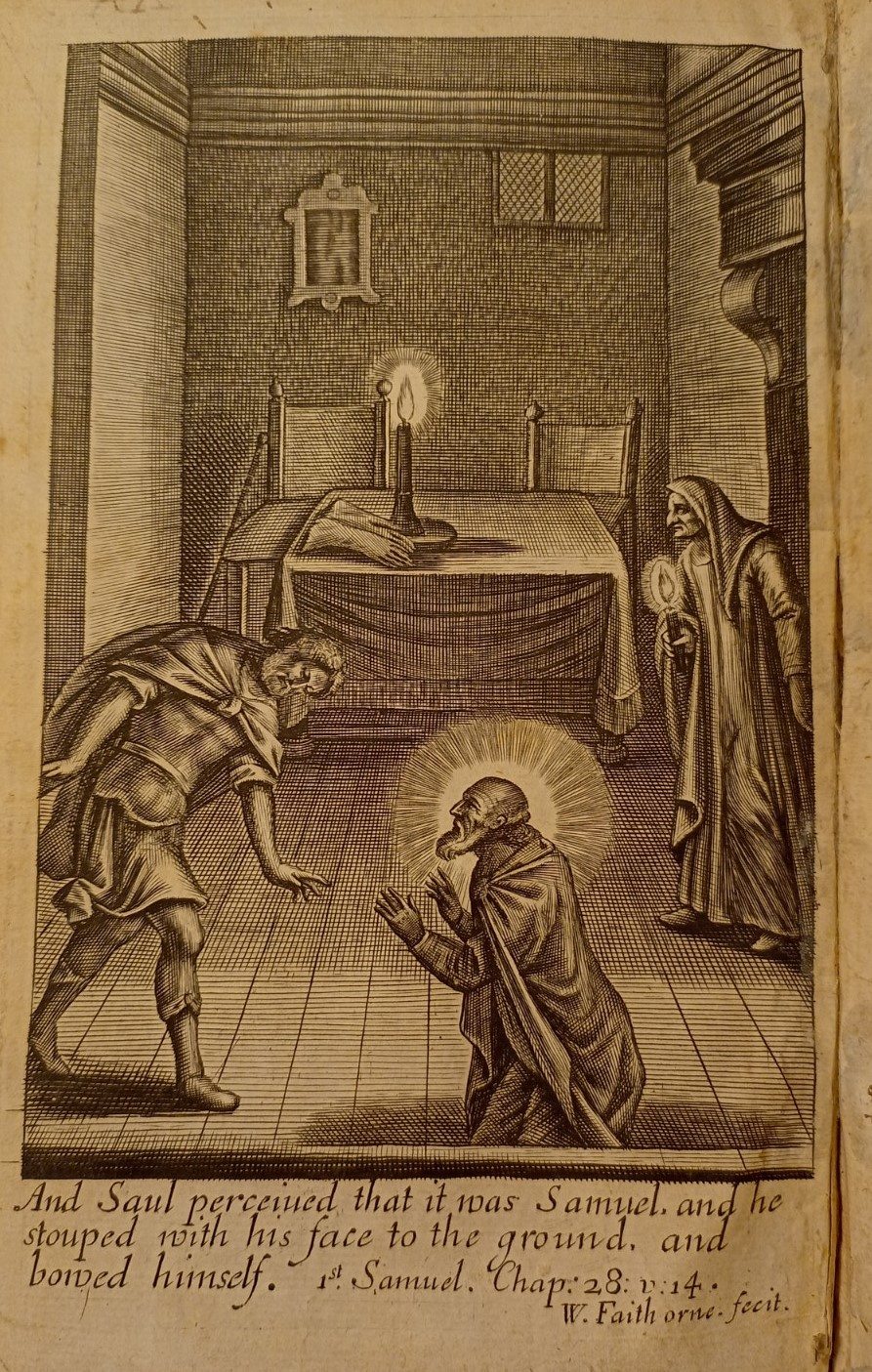

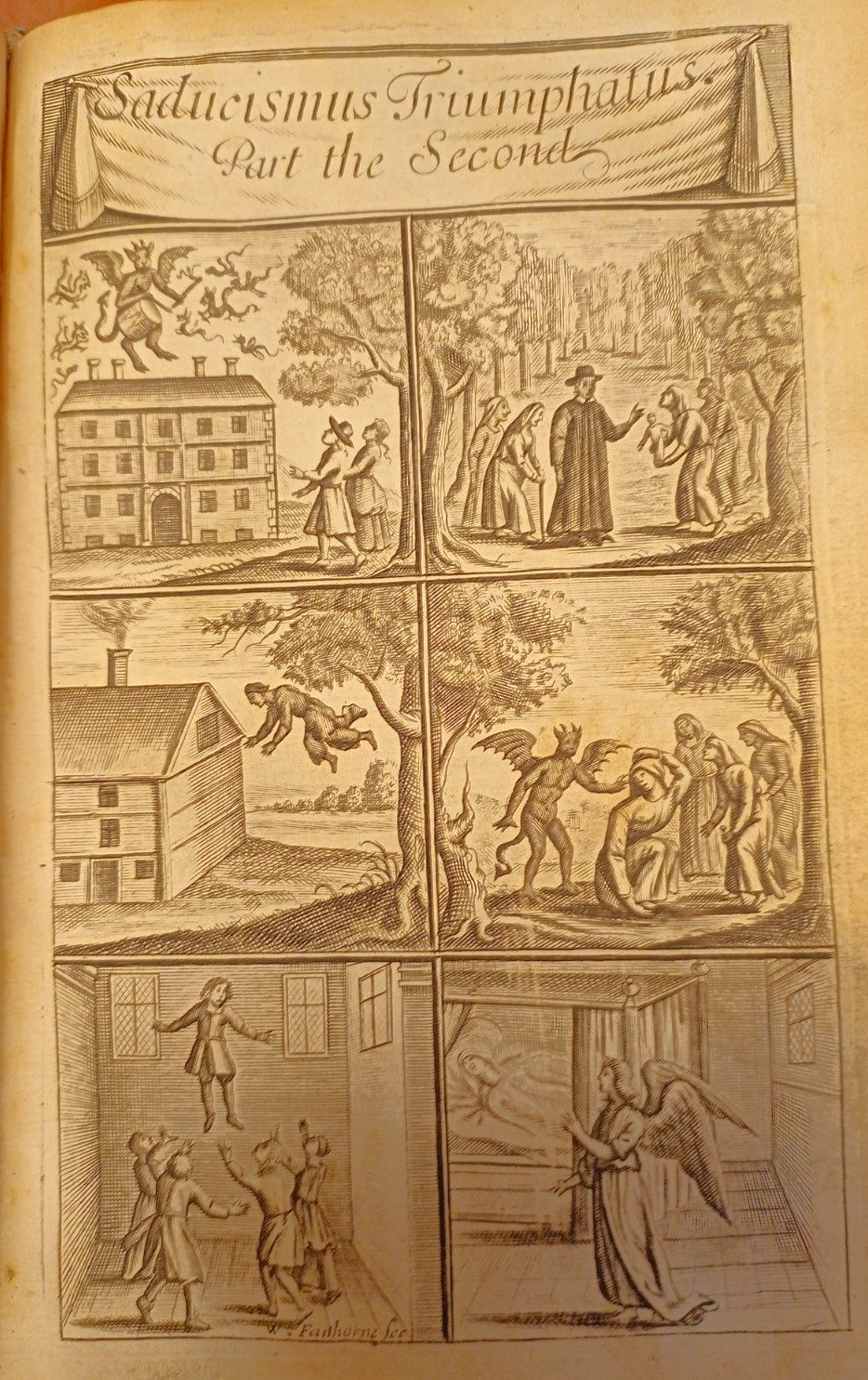

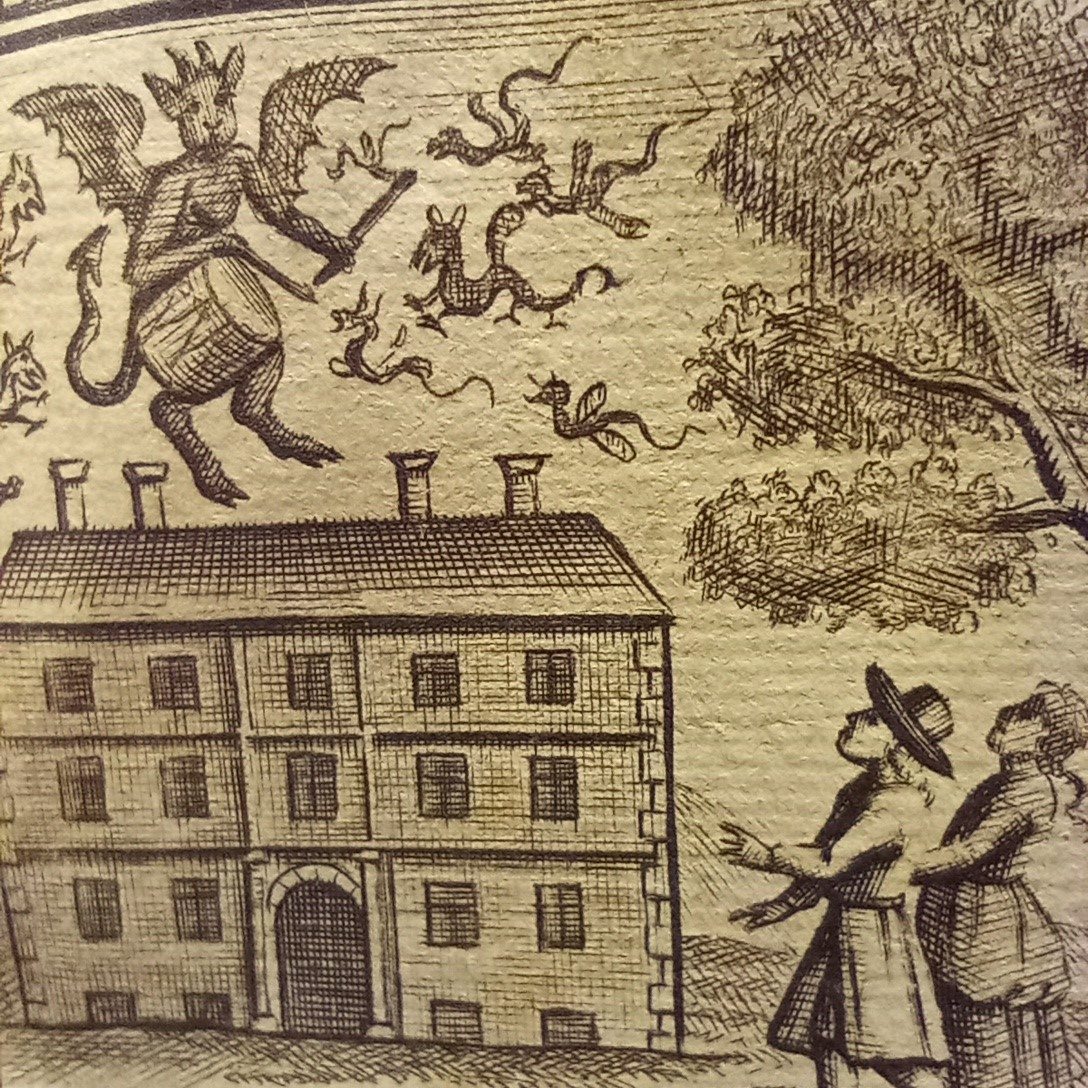

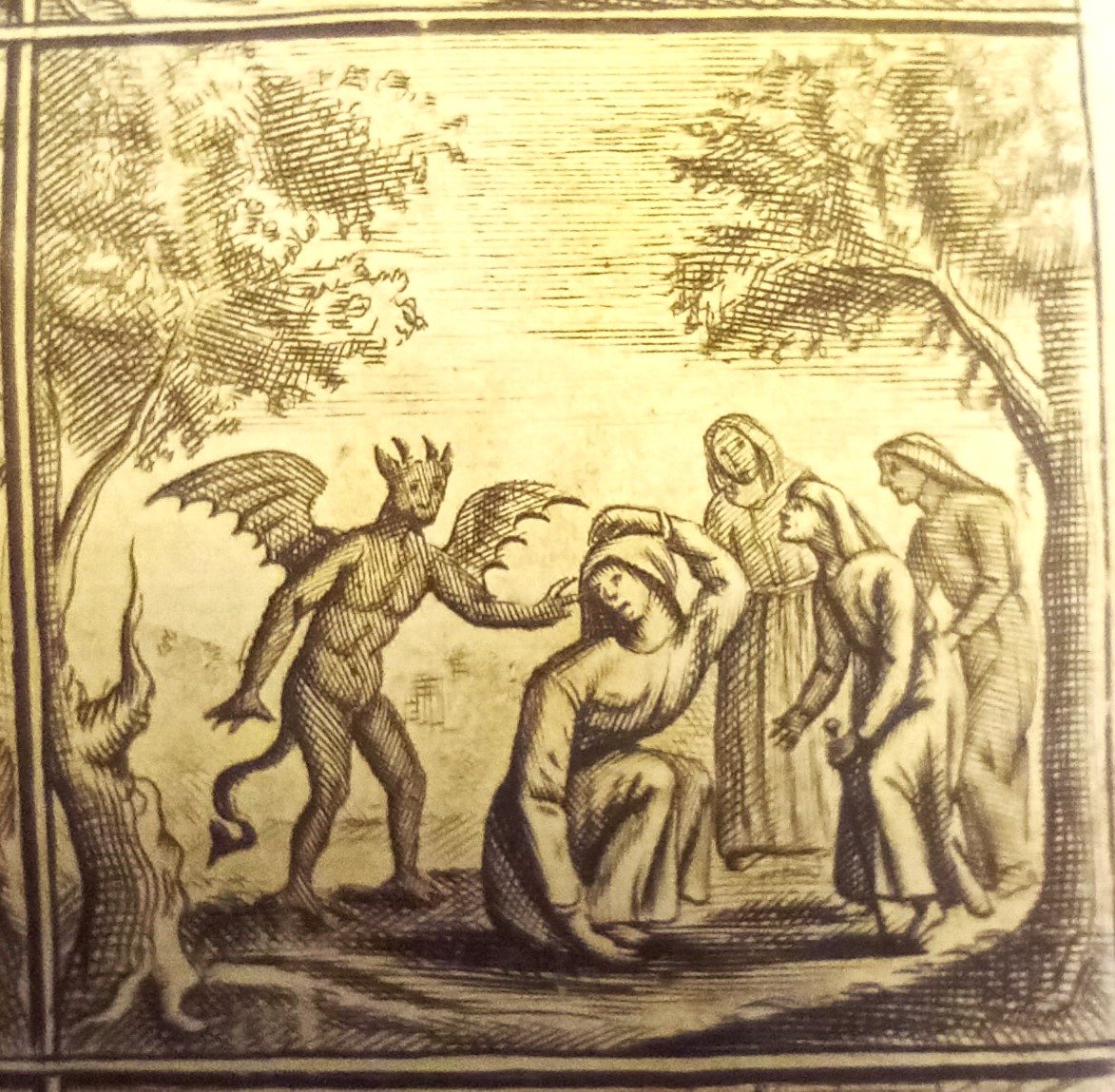

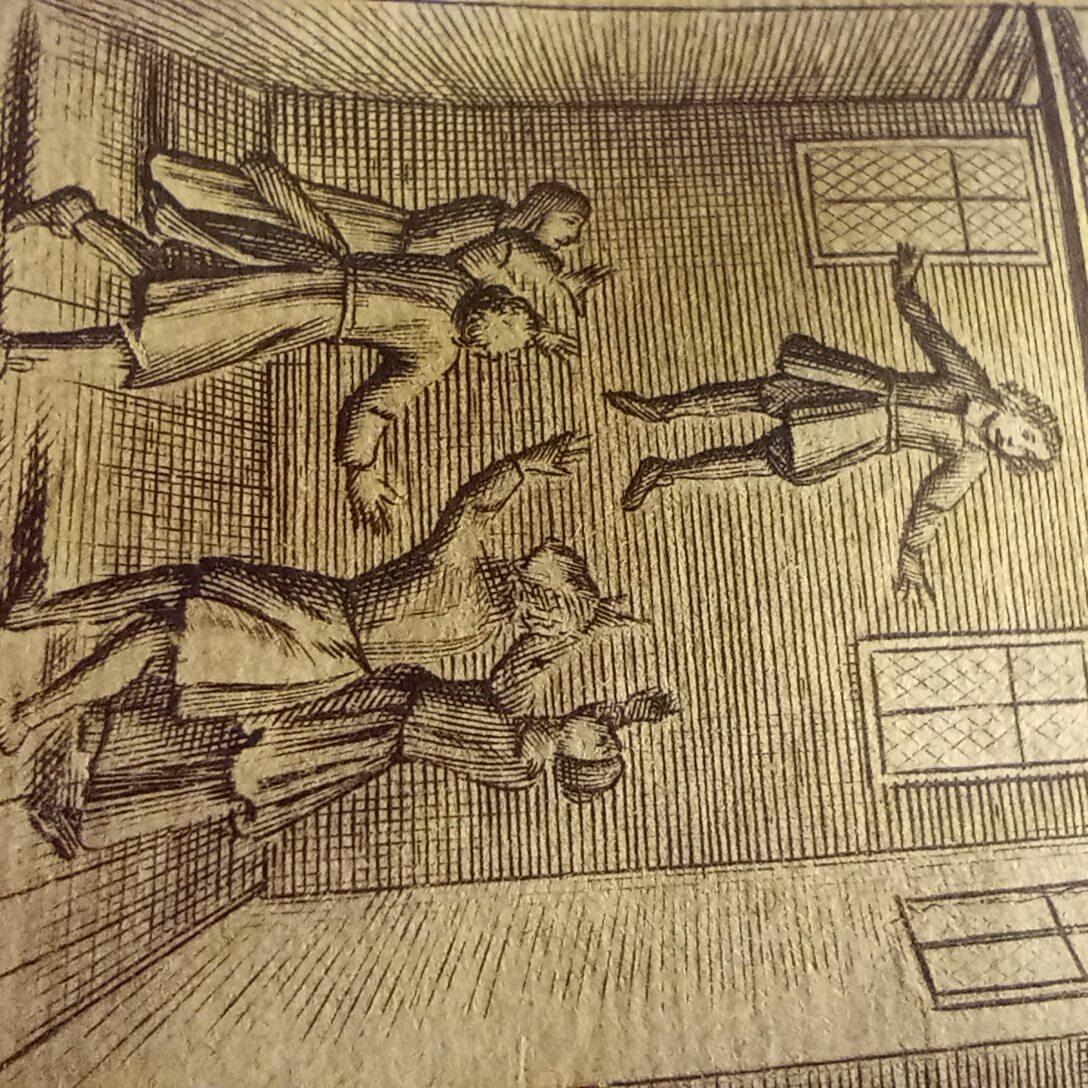

In spite of Glanvill’s endeavours to make his work appear a serious, academic text on the subject, his “choice collection of modern relations” of supernatural incidents contains all the implausible dramatics expected from a work on witchcraft. Phantom drummers, women flying through windows, and levitating furniture make up just some of the mysteries in this book. Several tales are concerned with the use of witchcraft on children, often a child accusing a woman of being present when they developed an illness or fit. Some of the women, when tried by a jury, confessed to these crimes, perhaps hoping for a lighter sentence. Several of them were executed. Other tales relate the appearance of ghosts; a murdered man seen in the cell with his murderers, family members returning to right wrongs, or suggest a better path.

Against the historical setting of witch hunts and executions, these fantastic stories take on a darker tone. Glanvill himself admits that “other Witch-finders have done much wrong […] Torture [has] extorted extraordinary Confessions from some that were not guilty.” The second edition was published in the same year as the Bideford witch trial: 1682. Three women were executed on suspicion of witchcraft. It wasn’t until 1735 that the Witchcraft Act made accusing someone of witchcraft a criminal act, and thus abolished witch hunts.

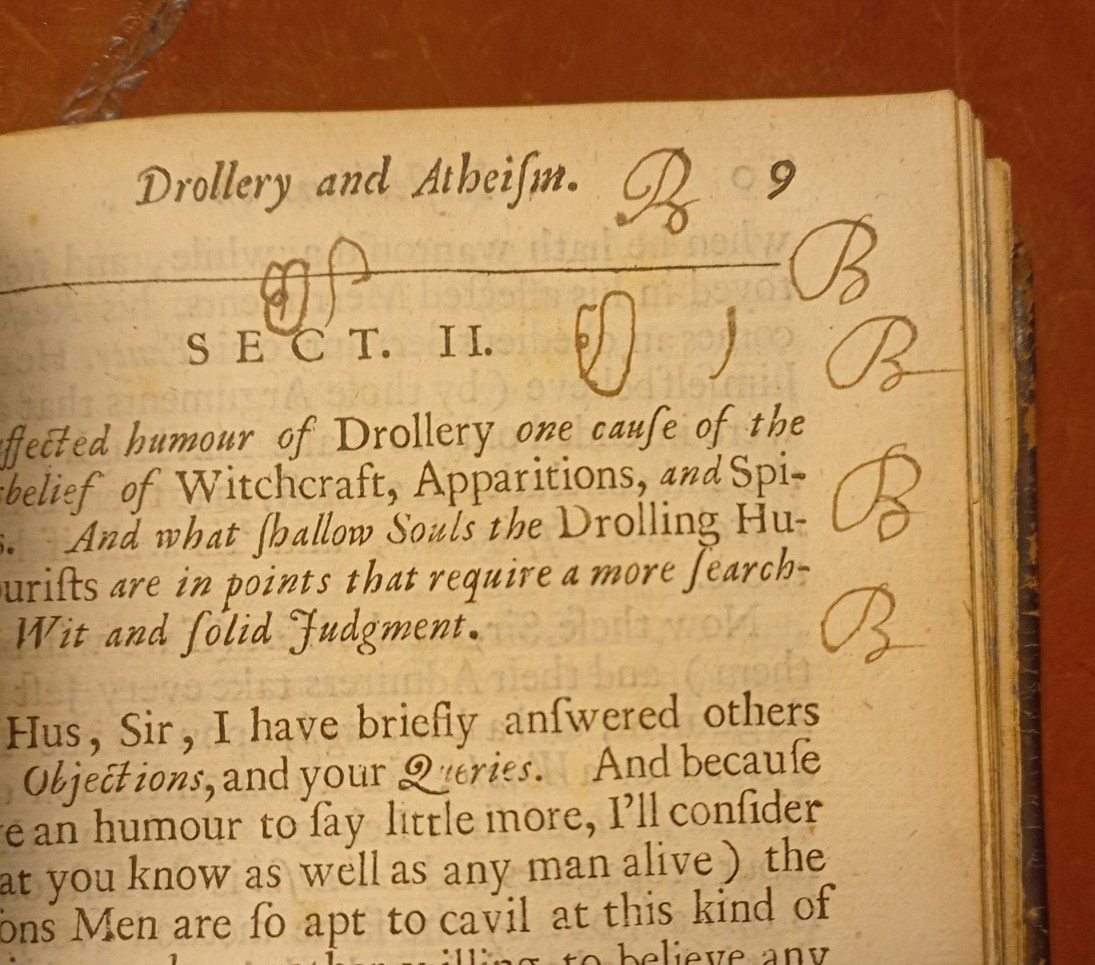

Although it is unclear when this book came to Caius, it has clearly been well-used in a past life: some pages have ink markings where a child has practised forming their letters in the margins. We hope that Joseph Glanvill, with his appreciation of science and learning, would appreciate his book having been used this way, and that it is still being studied to help us learn lessons from the past.