Mussels survive by developing thicker shells

- 19 February 2021

- 2 minutes

Having a thick skin is an oft-used phrase about resilience, but mussels have proven the old adage literally to withstand environmental and ecological changes, research by Caius alumnus Dr Luca Telesca has shown.

Mussels are important ecological and commercial marine species, and were the research focus for Dr Telesca, who completed his PhD at Caius and has now published a paper in Global Change Biology, titled: A century of coping with environmental and ecological changes via compensatory biomineralization in mussels.

Accurate biological models are critical to predict biotic responses to climate change and human‐caused disturbances, and Dr Telesca and his colleagues’ research explored the ecological responses of a species at a local level, in adaptations measured over 100 years.

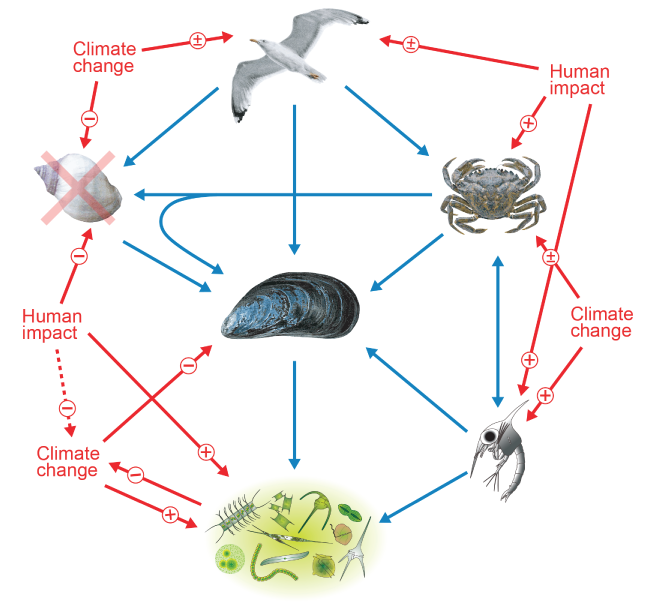

Dr Telesca studied 268 specimens, which had been collected regularly from a 15-kilometres long section of the Belgian coastline between 1904 and 2016. His results showed that the humble blue mussel is fighting to protect itself from environmental change and increased predation from seagulls by building itself a thicker shell. The unexpected phenomenon, tracked by researchers through generations of museum specimens, shows that climate change can have complex localised impacts that cannot be predicted by global experimental models.

Dr Telesca, who conducted the research whilst a PhD student in the Department of Earth Sciences and British Antarctic Survey, said: “There is no doubt that mussels are at risk of ocean warming and acidification – but we have also found that it depends where these changes are happening. Local human activities and environmental change can overlap with warming, resulting in unpredicted changes to communities of species.”

Previous research demonstrated a 1˚C temperature rise saw an increased shell thickness of 2 to 3%; Dr Telesca discovered a 57% increase in thickness when temperatures had increased by up to 3˚C in a century. The increase was attributed to a growing population of seagulls changing their habits from scavenging to predation, due to overfishing.

“They have to grab easily-accessible food like mussels,” Dr Telesca added in an interview on the Department of Earth Sciences website.

“What we are seeing is the mussels are clearly compensating for this shift in the number and type of predators – they are building thicker shells as protection.”

Dr Telesca’s research also hopes to highlight the importance of archival data in mapping future global climate trends to help scientists understand and respond to environmental change.

:: This is an edited version of a story which originally appeared on the Department of Earth Sciences website