Energy storage solution and the climate emergency

- 12 August 2022

- 3 minutes

The climate emergency and energy crisis have accelerated the necessity to improve batteries, with Gonville & Caius College Bye-Fellow Amogh Mahadevegowda making it his research focus.

Amogh was speaking on the hottest day on record in the United Kingdom in July. A further heatwave this week, hosepipe bans and water shortages were further reminders of the effect of the climate emergency and the demand for batteries to store energy generated from renewable sources to reduce the reliance on fossil fuels.

“Lithium-ion batteries can be a solution to the way we store energy and may contribute to a greener planet. Currently they are used in smartphones, laptops and electric cars,” Amogh says.

Batteries, of course, are made using finite natural materials and some of these materials are sourced via questionable mining methods. Amogh’s focus is on improving existing batteries, which will help to make the most of the natural materials used to make a battery pack, and on probing the next generation battery materials.

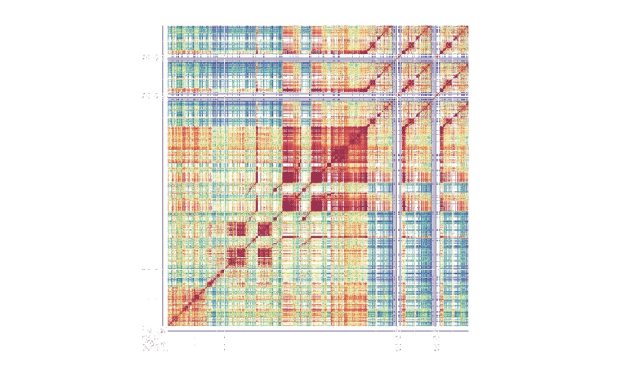

He adds: “We’re trying to understand how batteries degrade by looking at what’s going on at the nanoscale using advanced electron microscopes. This insight might help us to understand how we can prolong the life of a battery and hence reduce its overall carbon footprint.

“We are also trying to study new battery materials that can store more energy and have a low environmental impact.”

Given the interdisciplinary nature of Amogh’s research, he is working with colleagues at the University of Cambridge in the departments of Chemistry, Engineering and Materials Science, as well as contributors from other universities and industries.

Conscious that science often does not lead to policy change, Amogh is working with the Cambridgeshire County Council on their energy and economic policies.

“A lot of science we do in labs doesn’t necessarily have to stay in a research article. I think it has the potential to serve a greater purpose when it reaches people,” he adds.

Amogh was born and brought up in India before coming to the United Kingdom to complete his DPhil at the University of Oxford.

“The adverse effects of climate change are probably felt the most by the people who have least contributed to it,” he says.

“For example, countries such as India and Bangladesh have a low per capita carbon footprint. However, if the Himalayan glaciers that feed the Ganges melt at a relatively faster rate in the next couple of decades due to increasing global temperatures, then the scale of humanitarian crisis will be unprecedented as about half a billion people would be living in the Ganges River Basin. A large chunk of this population might also be displaced leading to a refugee crisis.

“I don’t think working on batteries itself is going to offer a complete solution. There’s a lot to be done by governments in terms of policies, and by us in the way we live and the choices we make.”