Oh deer!

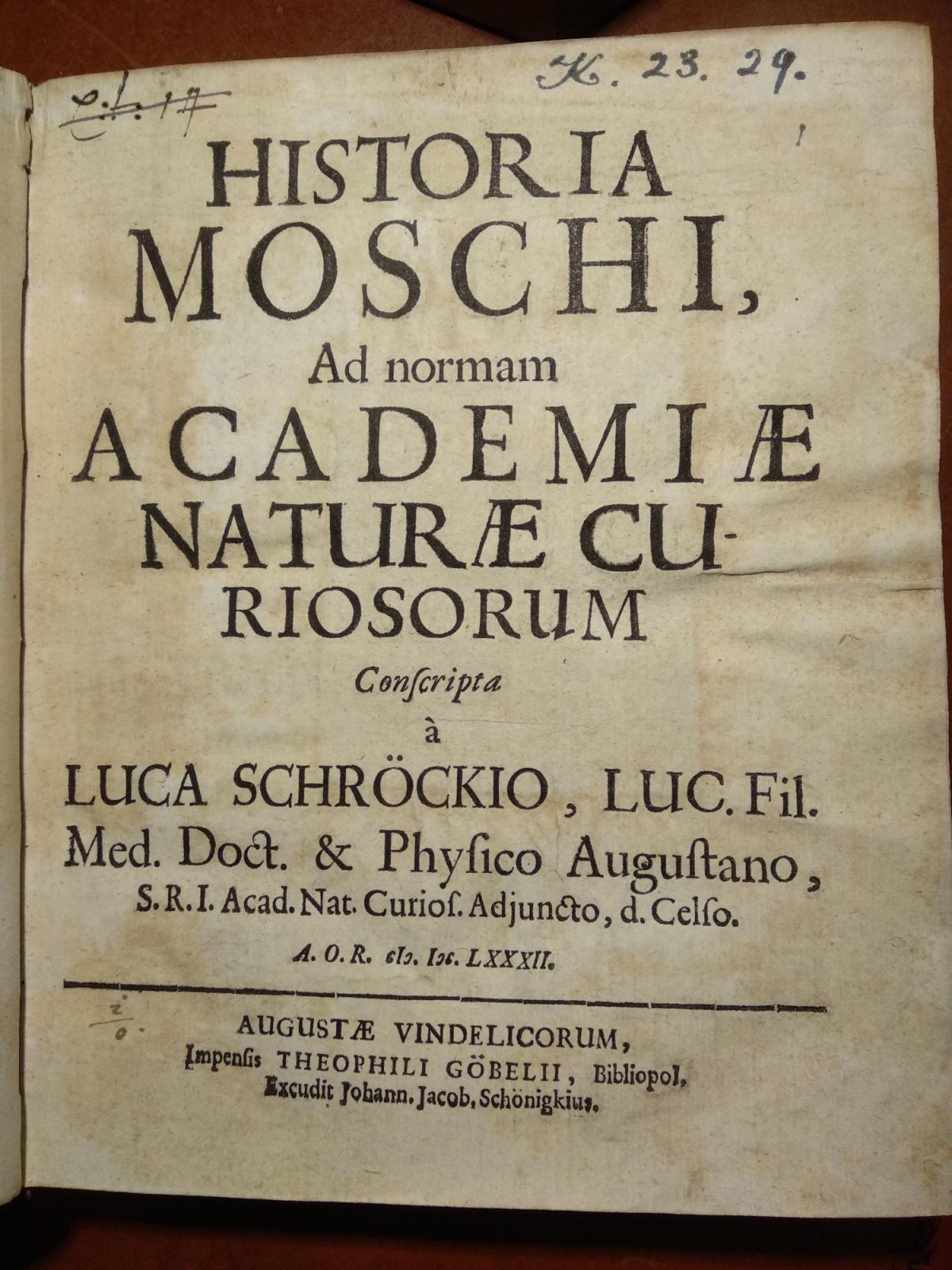

Historia moschi : ad normam academiæ naturæ curiosorum / conscripta à Luca Schröckio

Augustæ Vindelicorum : Impensis Theophili Göbelii, Bibliopol, excudit Johann. Jacob. J. Schönigkius, A.O.R. MDCLXXXII [1682]

K.23.29 ¹

In 1682 the Augsburg physician, Lucas Schroeck, published the book Historia Moschi or On the history of Musk. Citing both ancient and contemporary authors, the book is focused on the extraction of musk, not only from the gland of the Tibetan musk deer (Moschus moschiferus), but also from other animals.

Historia Moschi emerged from Schroeck’s Jena University dissertation on musk that he defended in 1667. While the dissertation was written very similarly to 1551 Gessner’s Historia Animalium, with a first chapter describing the animal and its habitat, this book is completely re-organised; it points out the many pharmaceutical aspects of the research, identifying and examining the different ways in which humans obtain and then use musk.

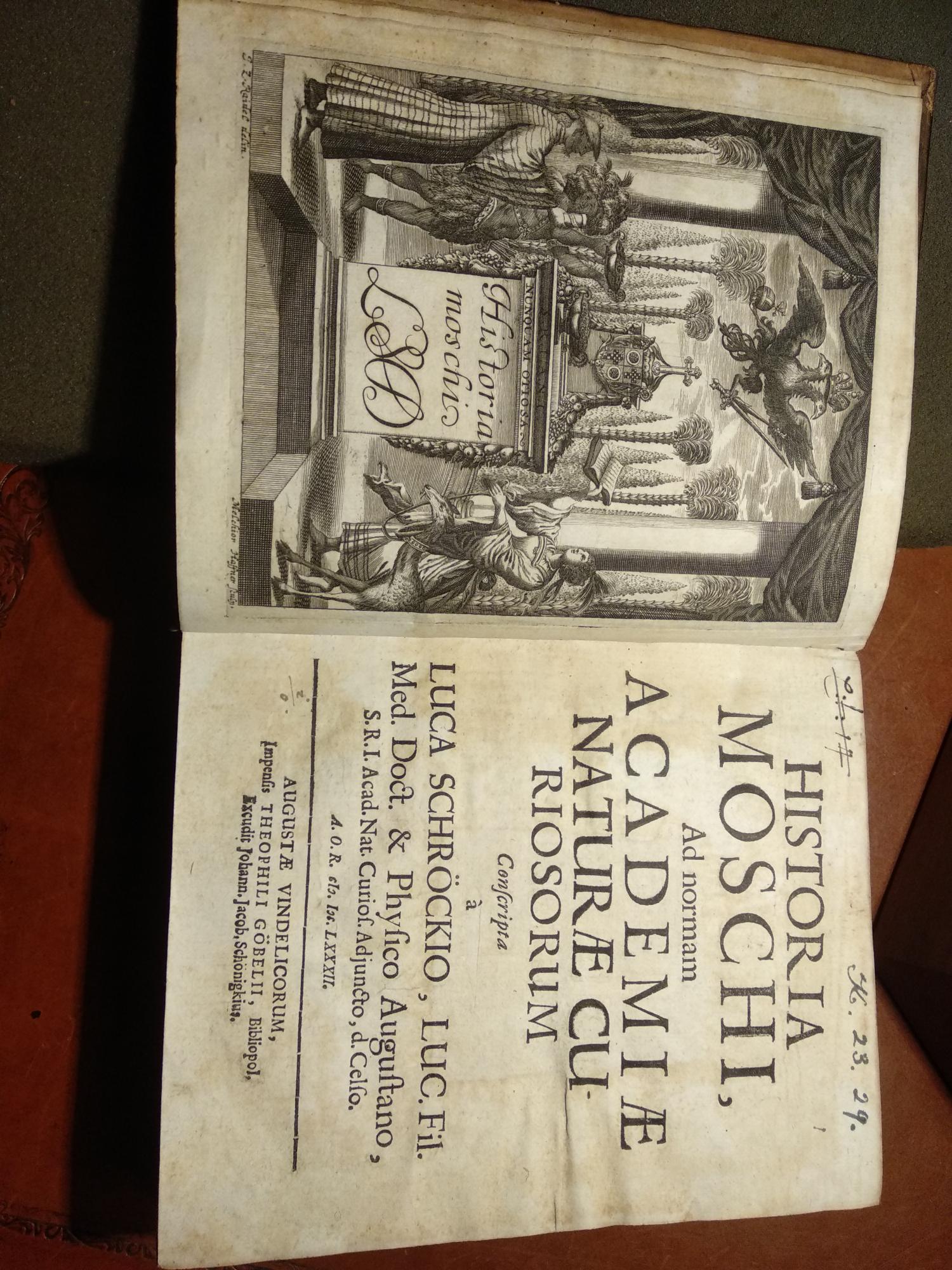

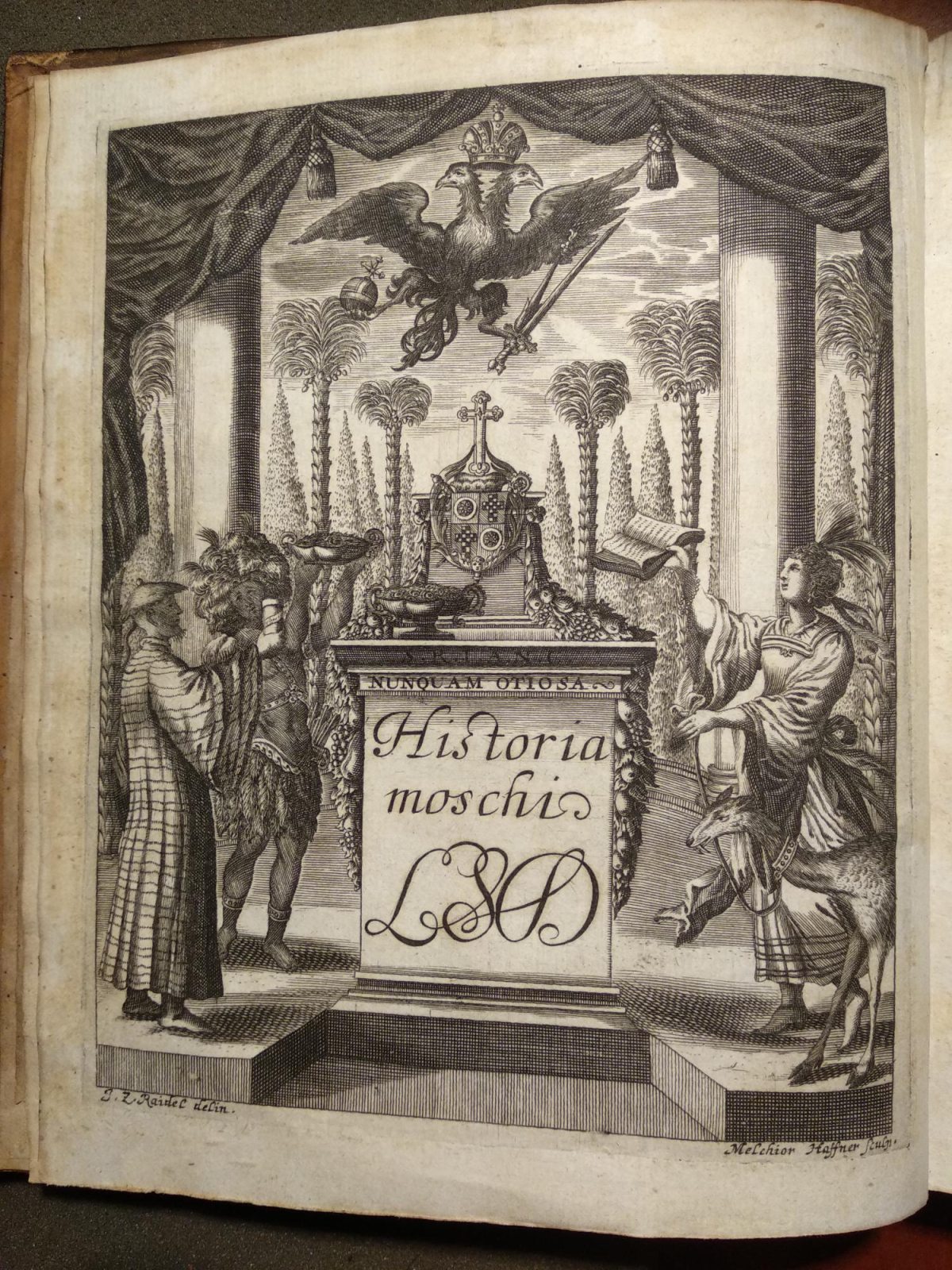

The book contains three high quality engravings by Johann Zacharias Raidel of Augsburg, which present the musk gland in detail. Historia Moschi was significant as it was the first time all the known information about musk from the literature of the time had been compiled into one volume. Enriched with contemporary anatomical and chemical discoveries made in several universities, the book stresses the practical and pharmaceutical benefits to human health of studying musk, showing clearly the developments in medical research between the mid sixteenth and late seventeenth century (Objects of Medical Collections: Musk, Prof. Anja-Silvia Goeing).

Musk has been used in traditional East Asian medicine and as a fragrance for over 5000 years. In Europe, thanks to its intensity, persistence and fixative properties, it has been used for hundreds of years in the perfume industry.

Musk is one of the most expensive substances derived from any animal in the world; its price today is double that of gold. It takes approximately 140 deer to produce a kilo of musk, and although it is possible to obtain musk from live animals, they were traditionally killed. Today Tibetan musk deer are protected by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora).

The biology of musk deer species is little understood, and their taxonomy uncertain. Initially classified with deer in the Cervidae family, today they are separated into their own family, the Moschidae. They differ from cervids for many reasons, the main one being that they have fangs instead of antlers.

The word “musk” is derived from the Sanskrit word Muskáh, meaning testicle. This famous secretion comes from an internal pouch, found between the rear legs of the male musk deer, and is used by the animal to mark their territory and attract female partners.

To obtain musk the “musk pods” are dried and the fatty-faecal grains inside it extracted, chopped and tinctured in alcohol for months or even years. This allows the musk to mellow and mature. During this process they lose their urine like smell and end up smelling fruity, floral, woody and sweet.

The provenance of our copy is unknown, but it is included in our 1731 catalogue, as is the companion volume which is bound with it.

The book has been digitised and the beautiful engravings can also be seen online (pages 67, 71 and 79).