By Professor David Abulafia

Professor Christopher Brooke, who has died aged 88, was one of the most prolific and influential medieval historians of the past 70 years. He came from the now vanished generation of high-flying historians who were not felt to need a PhD before embarking on their career; indeed, he held the title of professor for nearly 60 years, which may well be a record: he obtained his first Chair at the age of 29, at Liverpool, and later taught at Westfield College, London and at Cambridge. The time-span of his publications was even longer, for he published his first article (jointly with his father) in 1944, and he remained active in scholarship to the end.

At a time when the writing of medieval history has increasingly become dominated by ever more specialised monographs, Christopher Brooke demonstrated the importance of reaching out to a wider audience by way of well-illustrated surveys and much-used textbooks, although he was also a master of exact scholarship, with an especial penchant for the editing of Latin texts. His very successful From Alfred to Henry III, published in 1961, when he was 32 years old, had the great virtue of looking at England both before and after 1066. Europe in the Central Middle Ages (1964) displaced a standard account of the same period written by his own father; but it amply reflected a broadening in the study of the period beyond the popes and emperors who had dominated earlier writing to take in the social and economic history of Europe. In The Twelfth-Century Renaissance (1969) he made sensitive use of literary texts, dwelling with obvious approval on the tolerant world view of the great German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach, author of Parzival.

He wrote elegantly and unpretentiously, resisting the invasion of jargon; and he was not much interested in what is grandly called ‘theory’, recognizing much of it as the recycling of old ideas in highly ornamented new clothes. Sometimes, indeed, he wanted to tell a story, for example about Héloise and Abelard; but the analysis that accompanied the story was beautifully expressed and rich in insights. Yet he was perfectly open to new developments in the writing about the Middle Ages pioneered by such historians as Georges Duby in France, as can be seen in his book The Medieval Idea of Marriage (1989); and he was greatly respected in Italy. His profound sense of place was expressed not just in his writings about Cambridge but in the history of medieval London he co-authored with Gillian Kerr during his Westfield days.

He also demonstrated that medieval historians need not be confined, as has so often been the case, either to British or to European history, and that they have to take into account visual evidence as well as the texts of which he himself was so fond: illuminated manuscripts, architecture, archaeological remains. This might sound obvious today, but was much less so when the stern tradition of German medieval scholarship guided students towards the technicalities of charters and chronicles, sometimes barely moving beyond the intricacies of the documents themselves. Yet he was also an outstanding editor of texts, serving as one of the editors of Nelson’s (later, Oxford) Medieval Texts; his own editions of the letters of Gilbert Foliot (a famous figure in the Becket controversy) and of the great scholar John of Salisbury established standards that were rightly hard to follow.

To cap all this, he was a prolific historian of other periods as well, with a book about Jane Austen and her era to his credit, as well as a series of studies of the medieval and modern history of Cambridge University, which was his first and his last home. When he was elected Dixie Professor of Ecclesiastical History at Cambridge in 1977 he was aware that his was one of the few Cambridge chairs tied to a college Fellowship, in this case at Emmanuel; but he was also entitled to return to his beloved Caius as an ex-Fellow, which he did. He greatly softened the blow to Emmanuel by graciously offering to write a new history of that college, which followed on from a perceptive history of Gonville & Caius that navigated diplomatically through some of the crises and conflicts of the twentieth-century college.

Earlier, at Liverpool, Brooke proved to be both an inspiring lecturer and an inspired leader. There was nothing dirigiste about his leadership. He brought from Cambridge the idea that a Faculty or department should be run by democratic consensus and that professors do not exist to bark orders at their juniors. In Cambridge, he estimated that he worked ninety hours a week as a professor, and he was perfectly willing to sit on endless committees, notably as Chairman of the History Faculty, and as a member of the Divinity Faculty Board as well. He was an active Fellow of the British Academy and served as President of the Society of Antiquaries in 1981-4; he was awarded the CBE in 1995.

Christopher Nugent Lawrence Brooke was born on 23 June 1927; his father, Zachary Brooke, was himself a Lecturer (later Professor) of Medieval History at Cambridge and a Fellow of Caius, in whose chapel Christopher was baptized. Brooke was educated at Winchester and Caius; his father died while he was an undergraduate and Brooke was taken under the tutelage of the great historian of monasticism, Dom David Knowles, who had forgiven him for leaving a precious pile of his research notes on a bus at the age of 15; then, in 1949, he was himself elected to a Fellowship at Caius while serving as an Army captain. Knowles’s patronage had other dividends: he met his future wife Rosalind, who was writing a PhD thesis under Knowles’s supervision, and they married in 1951. She was a greatly respected historian of the Franciscan movement and of medieval popular religion, interests they shared; Rosalind died in 2014. He is survived by two sons and seven grandchildren; his eldest son Francis, died prematurely in 1996.

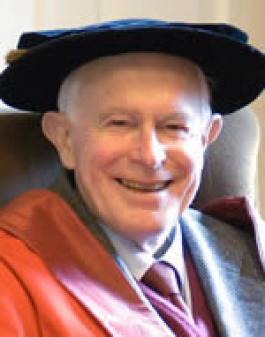

He was a handsome man, with a rather slight figure and an intense stare that, far from being intimidating, was curious and welcoming. His care for his students and younger colleagues at the three universities where he taught was legendary; he was generous with books and advice, but he also knew when to stand back and let younger historians do things their way. He kept an eye on them during their careers, and, if their children should happen to come up to Cambridge, he welcomed the next generation too to his sixteenth-century room in Gonville & Caius College, plying them with generous glasses of amontillado. Although he was deeply immersed in the three universities where he taught, he enjoyed escaping to his house at Ulpha in the Lake District. There he and his wife Rosalind could find the time, space and peace to write and to take delight in one another’s company.

A shorter version of this article appeared in today's Times newspaper.