Language changes in time and space

- 03 February 2021

- 4 minutes

The spread of new variants has become hugely topical during the Covid-19 pandemic. But for Dr Tamsin Blaxter the phrase is familiar and has an altogether different context.

“What I’m working on today is ‘Hierarchy Diffusion versus Contagion Diffusion’,” Dr Blaxter, pictured below, says on the day of this interview.

“These are terms borrowed from epidemiology, but we’re talking about the spread of new words and pronunciations, rather than viruses.”

Linguistic diffusion – the spread of new linguistic forms through speech communities – is the focus of much of Dr Blaxter’s work.

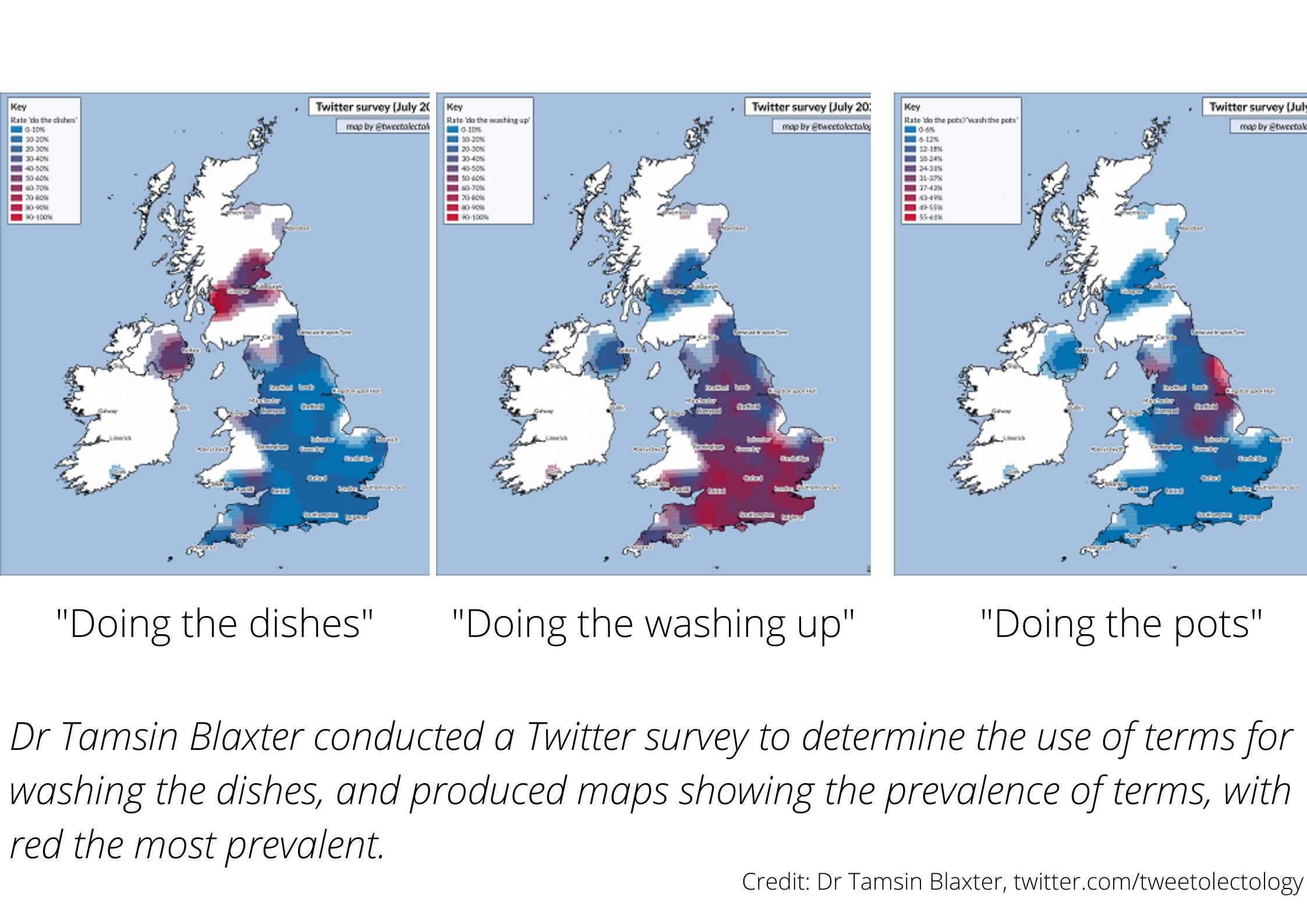

She is working on an ESRC-funded project entitled ‘Investigating the diffusion of morphosyntactic innovations using social media’, which uses Twitter to investigate language change in modern Norwegian, Welsh, British English and Turkish.

“A couple of connecting threads through most of my work are: looking at how languages change in space, if some new way of speaking arises in a particular locality, how does that new pronunciation or word spread to the rest of the region where it is spoken?” Dr Blaxter adds.

“I look at that in historical data, particularly the history of Norwegian. I also do stuff with modern English dialects: both change over the 20th century, and what we can see happening right now.

“Another thread is how digital methods allow us to get bigger datasets and answer bigger questions than we did in the past, and what statistical tools we need to do that, borrowing or developing tools from statistical geography for use in linguistics.”

Twitter, the micro-messaging social media tool, provides linguists with whole new ways of accessing data, and to reach people through surveys or algorithms.

Dr Blaxter completed her undergraduate degree in theoretical linguistics at the University of Essex, before completing an MPhil in General Linguistics and Comparative Philology at the University of Oxford. A PhD in Linguistics at the University of Cambridge followed.

“Language is this absolutely fundamental lens through which we see the social world,” she says.

“The way languages change, both hugely shapes the way communication works, and also the way we tend to think about people socially.

“People have all these biases about other people on the basis of the language they use, and those are often about new ways of speaking. These biases are largely just prejudices, not based on any kind of reality, so getting a better understanding on how languages really change, and work, is just good for society.

“It’s good that we are moving beyond negative assumptions about languages changing, or languages and class, which are intuitive ideas people hold. I hope by getting a better understanding of languages changing we can counter those assumptions.

“Within linguistics, there was a huge tendency to ignore space, and the fact that people live in places and that speech varies between those. That actually provides a huge amount of the explanation for why languages have evolved like they have. Getting a better understanding of the relationship between language and space is crucial.”

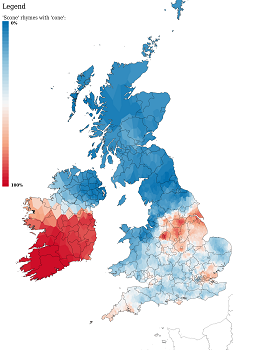

A map of the UK and Ireland showing the pronunciation of the word scone (red = rhymes with 'cone') (credit: Dr Tamsin Blaxter)

Language changes happen constantly, and Dr Blaxter has hypotheses about how the pandemic has contributed to how languages have changed, given people’s movements have been dramatically reduced.

She says: “In principle, language changing in space is all about mobility. For a new variant to spread from one place to another, people need to come into contact with one another, and that historically has required mobility, people literally moving from one place to another.

“Mobility has gone down drastically in the pandemic, so you might expect language changes to slow for a year. But mass communication and telecommunication have fundamentally changed the way in which language change works, in the sense that they make long-distance contacts much more common, so long-distance spread of new forms of language are much easier.

“Given that, I don’t think a lowering of spatial mobility for a year will make all that much difference, because that isn’t necessarily our main engine of change anymore, as it was for the whole of the rest of human history.”

Dr Blaxter was speaking ahead of LGBT History Month, an annual month-long observance of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender history, and the history of the related civil rights movements.

“Over the time I’ve been at Cambridge, and it’s reflective of a much wider societal change, there has been such a change in the visibility of Queer issues generally, and trans issues specifically,” adds Dr Blaxter, who is trans.

“Symbolic steps like flying the Pride Flag at the beginning of February, and symbolic steps like flying the Progress Flag specifically, really do mean a lot.

“Every year seeing photo collages of all the different colleges flying Pride Flags is a very uplifting moment of everyone coming together, or saying this community is trying to come together.

“These positive messages make people feel more welcome, and having a month where we all make an effort to do that has a real benefit.”