A chilling insight into a forgotten past

- 11 January 2022

- 7 minutes

Children as young as 10 were forced to jump from third-storey windows onto blankets or dive into the Baltic Sea, even if they couldn’t swim, as part of their initiation into the Nazis’ elite schools, according to a new book by a leading historian.

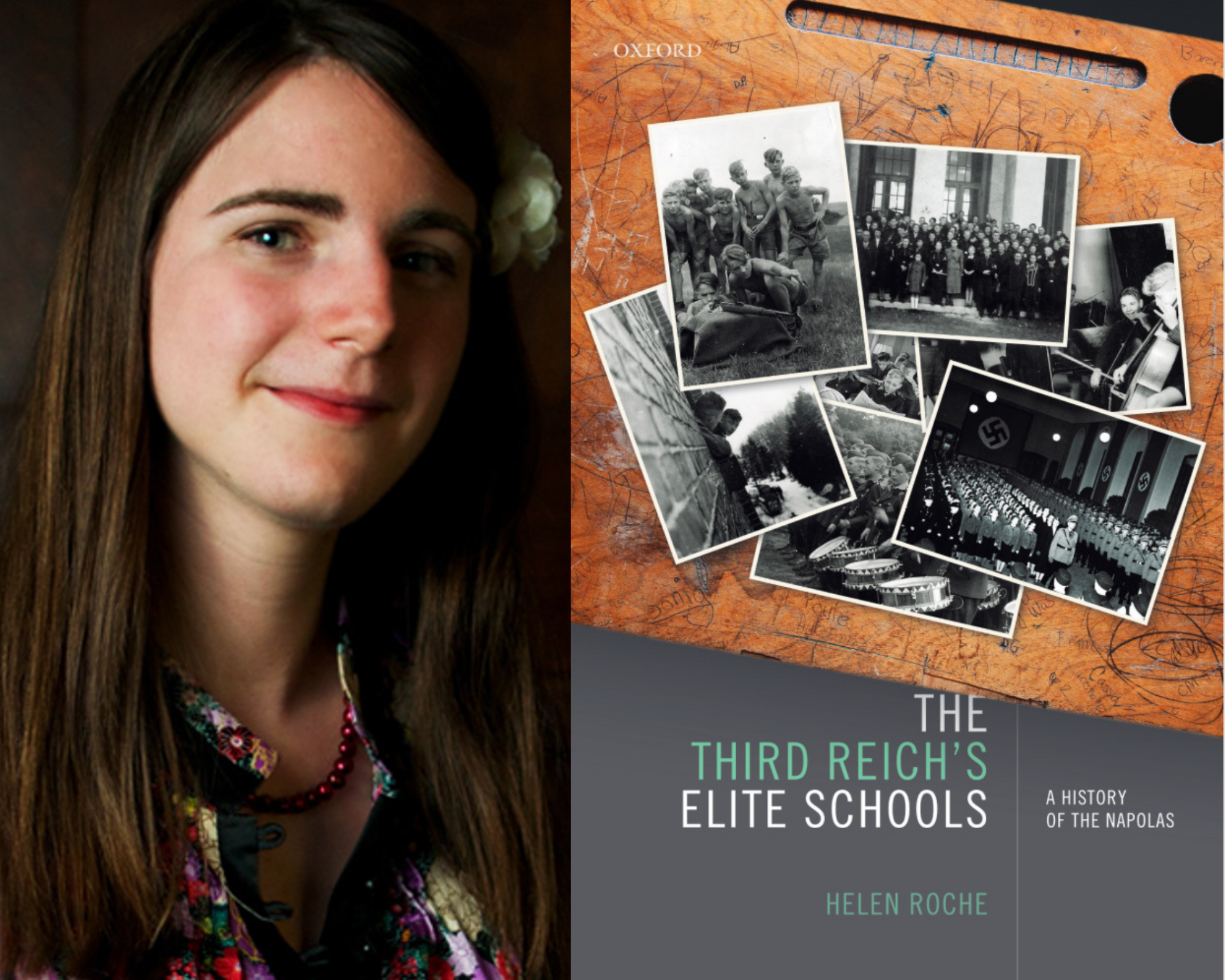

Dr Helen Roche (Classics 2004) has just published The Third Reich’s Elite Schools: A History of the Napolas. Her chilling insight into Nazi boarding schools reveals a slice of German history that has been largely forgotten – until now.

The Associate Professor of History at Durham University said she first became interested in the Napolas while studying for her PhD in Classics at Caius. Through her doctoral research – the book based on her PhD was entitled: Sparta's German Children: The ideal of ancient Sparta in the Royal Prussian Cadet-Corps, 1818-1920, and in National Socialist elite schools (the Napolas), 1933-1945 – she discovered that little had been published on these Nazi elite schools.

“I thought, well this is ridiculous, I’ve got this window of opportunity, where these former pupils are still alive and willing to speak, but that’s not going to last forever – in fact, several of them have subsequently died during the pandemic… I thought, right, I need to rescue this history,” she says.

A gruelling initiation

In her book, Helen draws on research undertaken in 80 archives in six countries, as well as eyewitness testimonies from over 100 former pupils.

Most had been recommended by their primary school teachers. After being observed by Nazi-approved staff, children would undergo gruelling pre-selection tests.

“They had to prove that they were of ‘Aryan ancestry’ and didn’t have any Jewish family members,” Helen adds.

“Then they had to be above average academically. There were a lot of physical tests, medical tests.”

The next phase was a week-long entrance exam at the Napola, involving academic and physical challenges.

Helen adds: “The most gruelling were the ‘tests of courage’, where prospective pupils would have to jump from a three-storey window into a blanket, or jump off a high diving board if they couldn’t swim. The whole point was that if you hesitated, you would fail the test and get sent home. They were trying to instil absolute obedience. Imagine being a nine or 10-year-old, going through that!”

Indoctrination

Many of the children came from working class or agricultural backgrounds, enticed by the opportunities these elite schools promised.

Helen’s research shows that the Napolas were far more effective at indoctrinating pupils than regular schools, the Hitler Youth, or other Nazi institutions such as the Reich Labour Service – largely due to their segregated nature. Every activity was intended to politicise the students.

Up to 50 younger boys might be crammed into a dormitory, supervised by an older prefect.

“Sometimes these boys were kind to the younger ones, but sometimes they became tin-pot tyrants who would also bully them,” Helen adds.

A typical day would start at 6am with a run around the grounds, followed by a flag parade and roll call. After breakfast, children would attend an ideological assembly and lessons, followed by lunch. Afternoons would be taken up with sport or pre-military training, followed by supper and homework.

But it didn’t end there. Boys would often be stirred from their beds in the middle of the night to take part in ‘Geländespiele’ (war games).

“You’d have two teams and they’d have a coloured thread attached to their arm. If someone tore it off, they were ‘dead’,” she adds.

Early pre-military training was disguised as outdoor education in the form of ambushes, hiding in undergrowth and attacking the enemy.

“One of the things that I was trying to do in the book was to show why people might have found this form of education so seductive at the time, even though obviously it’s all in the service of an evil regime,” Helen says.

“It was deliberately presented to be fun for the smallest children… As they get older, the training gets harsher, but it still has that element of a game. And then they go to the front, and suddenly they’re hit with all of this horror and actual death, which none of this has actually prepared them for.”

Mixed memories

While some ex-pupils were traumatised and remorseful, others described their schooling as “some of the happiest days” of their lives.

“There was a really wide spectrum of reactions… Others have said, ‘we know now that we were being trained to become potential murderers or do anything in the service of a terrible regime, and so I want nothing more to do with it,” Helen adds.

Some interviewees had ‘whitewashed’ their history as a coping mechanism, trivialising the role the Napolas had played. But the Third Reich had used these schools to mould its youngest recruits, Helen says.

She adds: “Some of the Napolas were trying to obtain furniture from deported Jewish families to furnish new school buildings. Some of the students took part in anti-Semitic campaigns. It was a wholly racist mode of existence.”

Helen’s interviewees tended to be in their early to mid-teens in 1945. The historian said she might have found it harder to interview older students who had served in the SS, particularly given her own partly Jewish heritage.

The British connection

Archives show that the Napolas drew inspiration for their elite boarding schools from British public schools, with pupils taking part in exchanges and sporting tournaments with boys from Eton, Harrow, Winchester, Westminster, Rugby and the Leys School in Cambridge, between 1934 and 1939.

Helen adds: “This wasn’t a history that anybody really knew about… You get accounts of a fencing team coming over from Eton or Harrow and they get a speech from the Nazi headmaster about how Britons and Germans need to stick together as representatives of the white races – terrible stuff. But there are actually numerous accounts of these exchanges, even from the Leys School in Cambridge.”

As Anglo-German relations deteriorated, relationships between the schools became fraught, but even towards the end, some on the British side wanted to believe in German good faith, Helen says.

“With hindsight, you’d see it as quite naïve,” she adds.

Full circle

Dr Roche has come full circle – now teaching at Durham University, where her father once taught in the Music Department. It was after a brief stint in Italy at the age of seven that she became fascinated with foreign languages – a pathway she explored when she studied Classics as an undergraduate and postgraduate at the University of Cambridge.

She applied to Caius after attending the choral open day. A violinist, viola-player, organist and choral scholar, she particularly enjoyed her time in Caius Choir, which included a tour to the United States during her second year.

Having specialised in historically informed performance, towards the end of her PhD, Helen took part in a side-by-side scheme with the Academy of Ancient Music, playing alongside their principal viola.

“That really was one of the greatest experiences of my musical life. When you’re playing with such amazing people, it’s just an overwhelming experience – you’re part of this world class ensemble, playing beautiful music,” she says.

She also recalls an incident where “a massive bowl” of strong punch was smuggled past the Porters’ Lodge at midnight in a shopping trolley, following a College concert.

“We took it back to Harvey Court and people were on the balconies, riding around in the trolley!” She says.

An “amazing community”

The Caius alumna is still friends with former Director of Studies in Classics Dr Richard Duncan-Jones, and German History Professor Joachim Whaley, and has kept in touch with many of her College contemporaries.

She remembers popping into the Porters’ Lodge regularly to “get all of the College gossip”, and was particularly touched when her bedder brought her an embroidered purse after a visit home to her native Philippines in second year.

“The College is an amazing community, not just your fellow students and the Fellows, who are obviously amazing, but also the wider support staff and the Porters – everyone makes it what it is,” she concludes.

The Third Reich’s Elite Schools: A History of the Napolas, is published by Oxford University Press.

Archive photographs credits: Dietrich Schulz.