Illustration

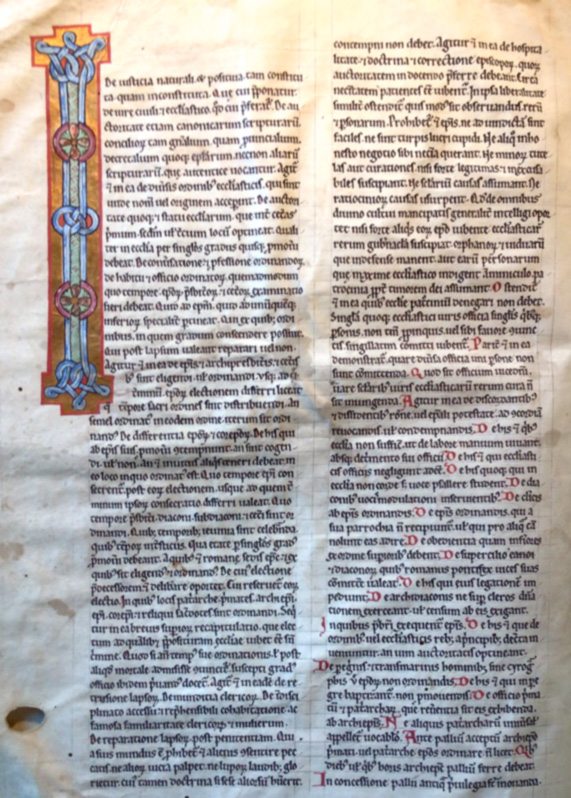

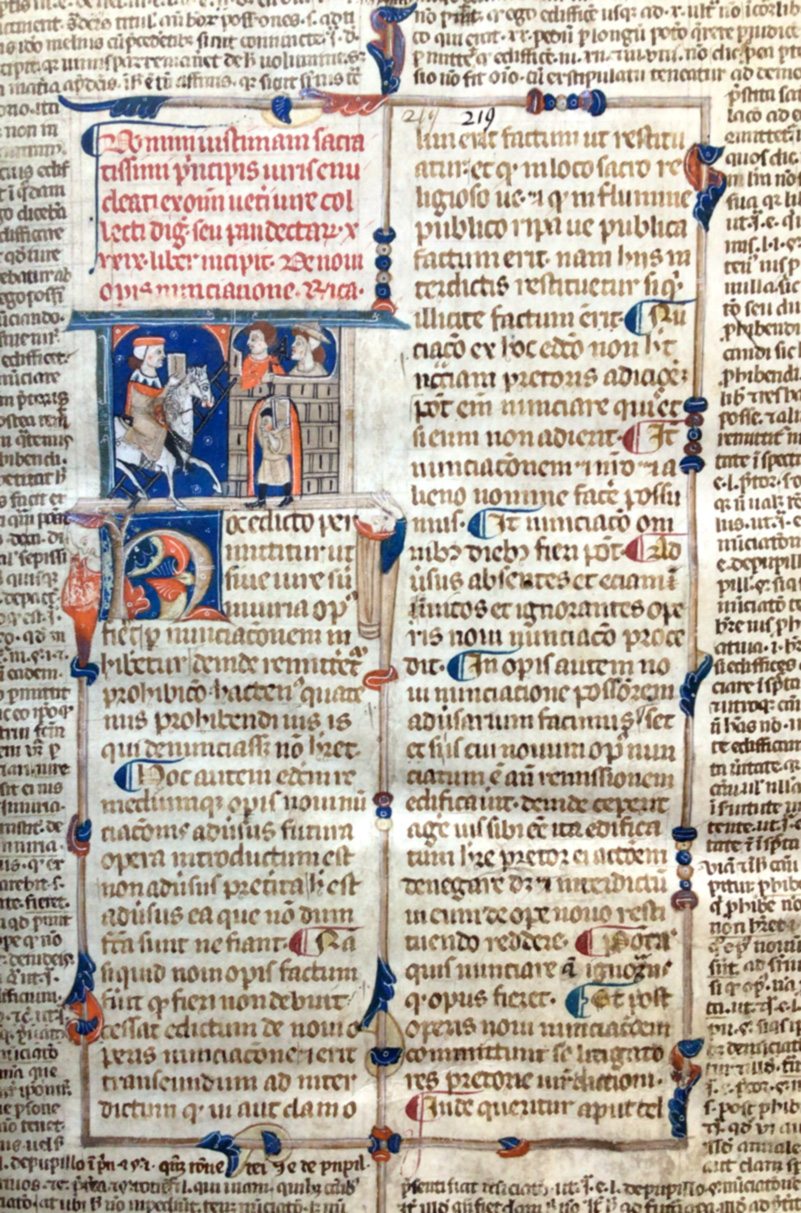

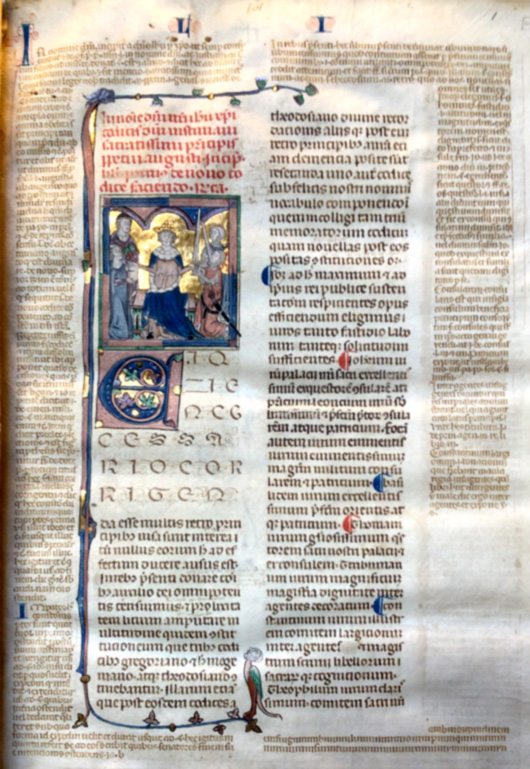

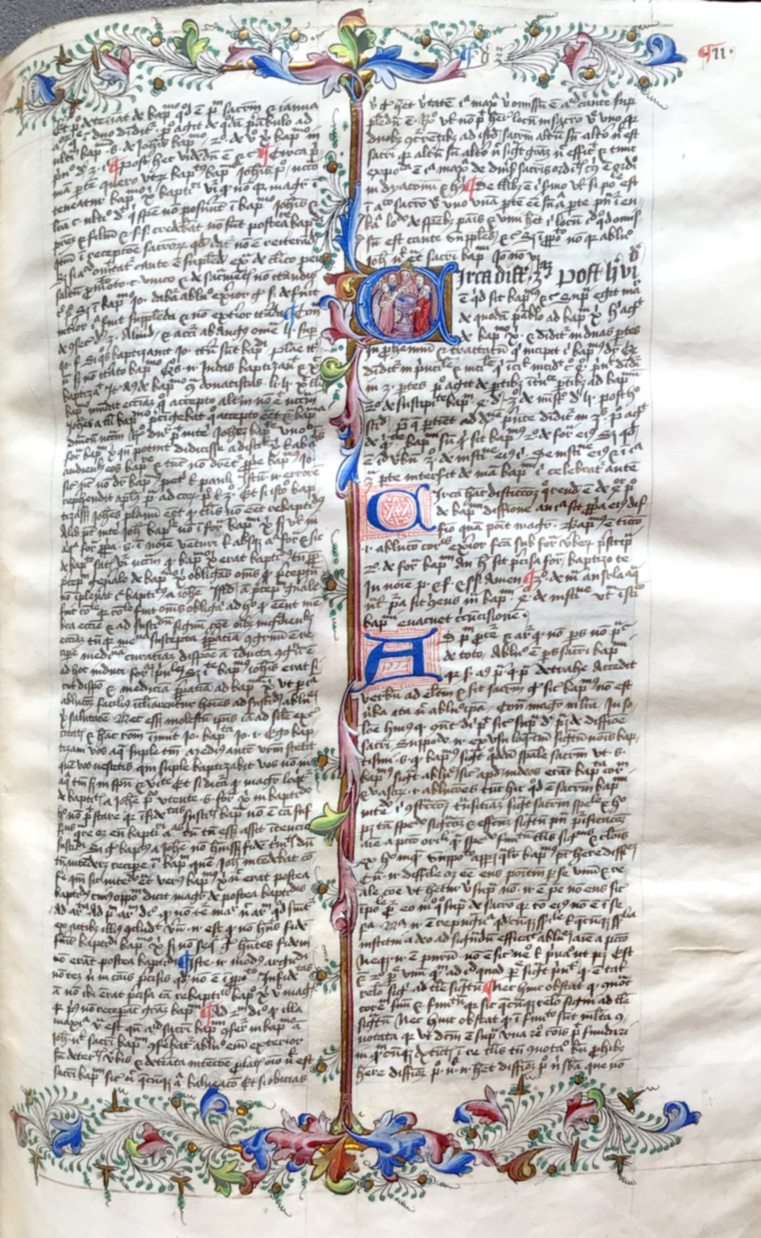

The main purpose of illumination in books was to glorify holy manuscripts and to ornament the text, rather than tell a story. The Lindisfarne Gospels, the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow and the Winchester Bible are some of the best examples of elaborate manuscript illustration, containing miniatures and highly ornate initials which could extend the full length of a page.

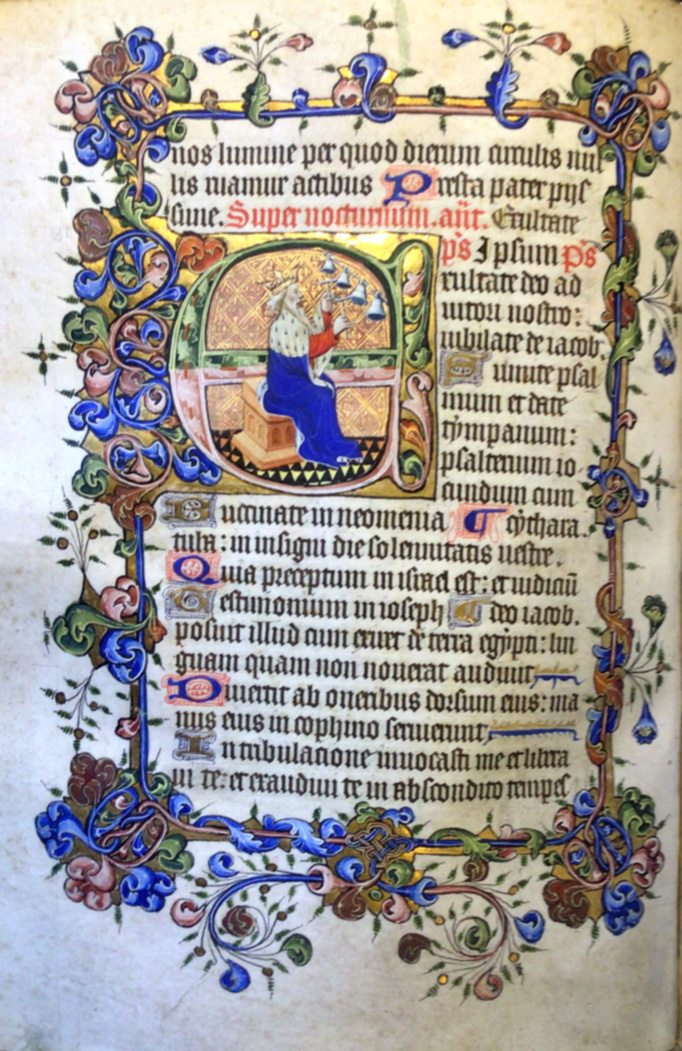

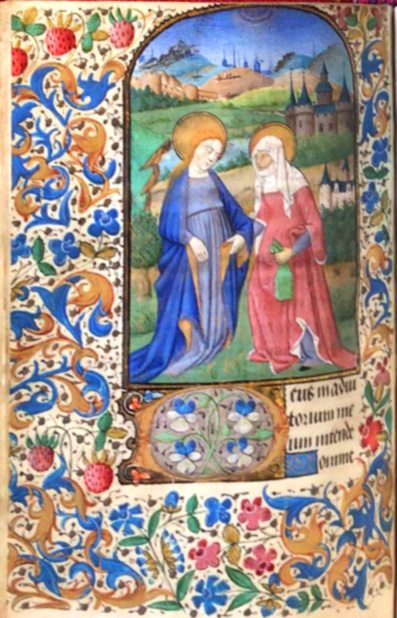

Books of hours which proliferated in the 14th & 15th century were so beautifully illustrated and illuminated that they were likely to have been the objects of great religious devotion. The quality of these psalters might indicate the importance of the owner who could afford them – but it is also likely that they were produced in this way to glorify the content, which would have been sacred to the owner. Readers would kiss the icons in the images, as can be seen where faces of saints or the holy Cross have been rubbed away.

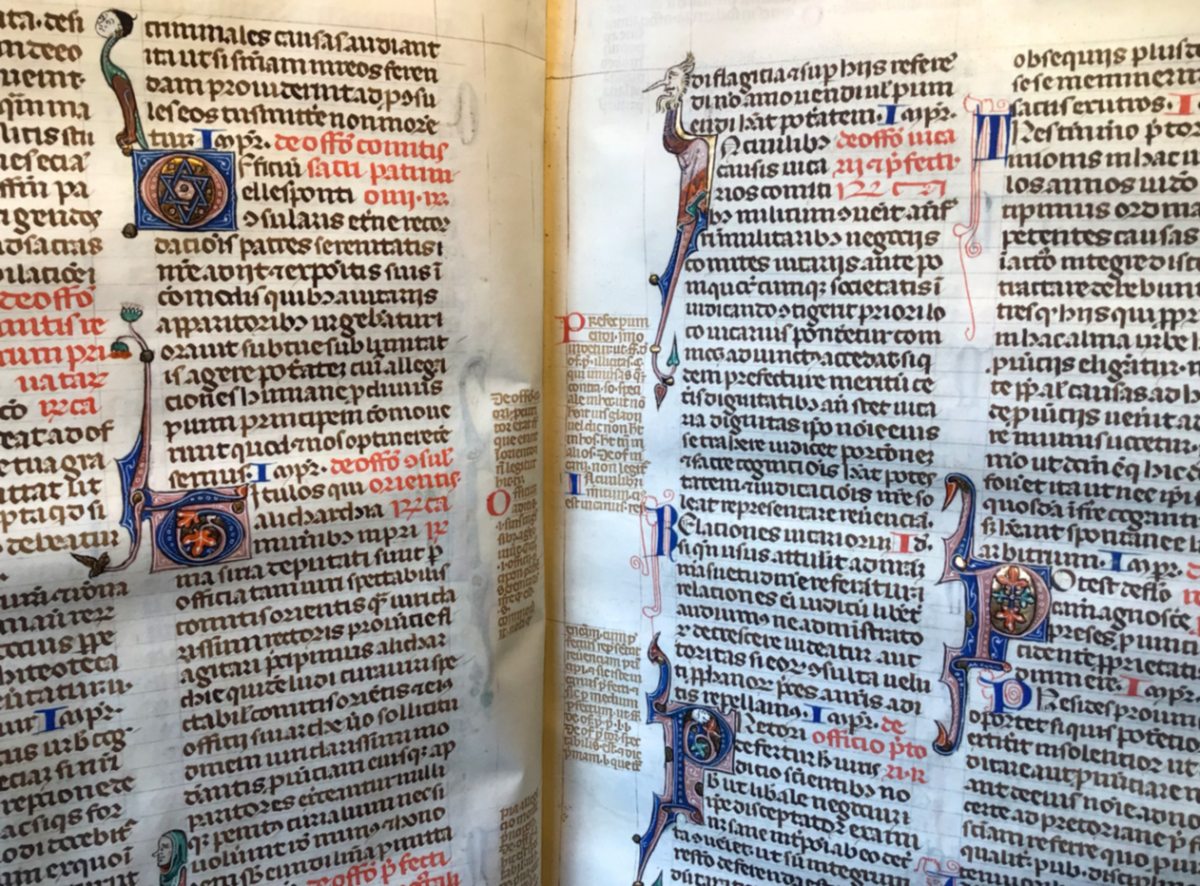

Illuminators were employed to decorate manuscripts after the scribes and rubricators had completed the texts. Like the scribes, their skills were highly prized, and towards the end of the 14th century women as well as men were employed in this craft. However the ornate style of manuscripts changed with demand. Once monks were required to travel and preach they needed more portable copies of the Bible. Small single volume bibles appeared written on extremely thin parchment and with very small lettering. Manuscripts for the use of scholars of the middle ages were not usually the highly decorative volumes mentioned above; but copies made hastily for practical use, often by the scholars themselves.

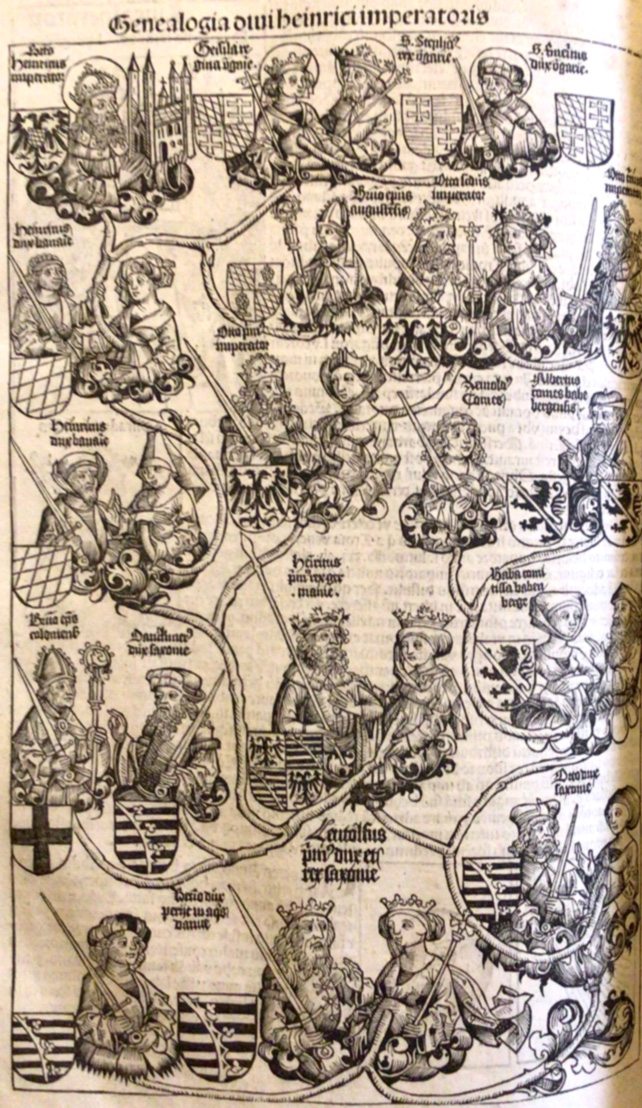

The manuscript process of hand illumination could not begin to scale to print production, so to illustrate their books printers took up Europe’s first mass medium, the woodcut. The woodblocks from which they were printed could be set up alongside type in the press, although there are early examples where woodcuts were printed into spaces left on the page, and sometimes further annotated by hand.

Woodblocks were very durable and could be used repeatedly: a printer might obtain tens of thousands of impressions from a matrix. The Nuremberg Chronicle (1493) shows how 650 woodblocks were used over and over again within a single book, to illustrate cityscapes and portraits. With the advantages of woodcuts however came the loss of colour, one of printing’s greatest problems (see also section 3, Typography). To include colour meant running the pages through the press several times, as each one had to be printed separately.

Lozenges and panels might be left blank when printing, to be filled in later if required by the purchaser. Illustrations, patterns, and colour could be added post-production. Patterns for initials and borders were standardised allowing for repetition of these patterns with minimal effort.

Some illustrators/illuminators became popular as independent workers during the transition from manuscript to print. Miniaturists in Venice had well established reputations in the 1470s, and would take on individual commissions. Others were contracted to the printing houses, or had working arrangements with them. The number of illustrators would have increased at this time, but decreased again as printing techniques improved. The days of the beautiful illustrated manuscript were coming to an end and even the most modern colour printing has never been able to replicate the full beauty of their brilliant colours and textures.